n

Add to this list of misery is the fact that none of the top five class “A” orchestras has a recording contract with a major label at this time. That in itself is a litmus test of just how far the industry has sunk; 20 years ago they all had at least one contract with a major label. In fact, the only recent American recording project of any magnitude I can think of is the outstanding Mahler Symphony cycle by the San Francisco Symphony completed several years ago. Mind you, the only reason it was ever accomplished was because the recordings were released on the symphony’s own label and the entire project was underwritten by the Getty foundation. Otherwise, it would never have happened.

Why is the state of the state so dire for American orchestras and classical music in the U.S. in general? Lots of reasons, but the first has to be cost; the average annual salary for a top orchestra is upwards of $100K. Multiply that by 75-100 people, add benefits on top of that, and you can easily see that running a major orchestra is a multi-million dollar excursion and one that simple ticket sales can’t completely support. Historically, American orchestras have been subsidized by the feds. But that funding has dramatically decreased in the last decade, most notably in the last several years coinciding with the world economic meltdown.

Listening audiences, specifically those that actually attend a “live” concert by a major orchestra much less buy a recording, aren’t getting any younger. Other than having a young rock star conductor like Gustavo Dudamel in Los Angeles, there doesn’t seem to be any major impetus or vehicle to get younger audiences listening to classical music or going to concerts. Likewise, in the past composers and compositions were cyclically being “rediscovered” by movie audiences as elements of soundtracks, but that doesn’t seem to be happening as much now.

I’d also like to put forth that the way younger generations listen to music now probably has something to do with all this. To point, listening to music is not the singular experience I grew up with as in sitting down in front of some speakers for a duration of time—and listening. Now the music experience is generally defined as downloading single songs, creating playlists of different songs/artists, and listening to music through ear buds to an iPod, iPhone, or other smart phone-like device. Further, listening to music is often done on the go with any number of other things going on in the moment. One might be tempted to ask if listening to single songs and multi-task-listening makes for a shorter attention span or at least a different kind of attention span.

Here’s what I want you to do: go out and download or even purchase a CD of Mozart. It’s easy. Not sure what to buy? Not a surprise given our beloved Wolfgang wrote almost 700 published pieces in his altogether too short of a life span—as in less than 36 years. That’s the bad news. The good news is that I’ve put together a short list of favorite recordings to make it easy for you. I also just checked on iTunes and many of them are available there. Otherwise, mosey on over to Amazon for the recordings. You’ll be glad you did. Mozart does indeed make you smarter.

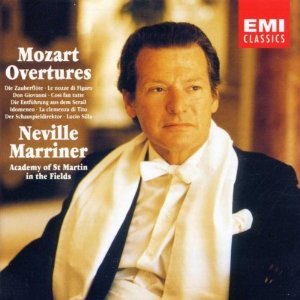

Recommended pieces and recordings: there are multiple recordings of all the pieces I’m suggesting but know that all recordings are definitely not equal. In fact, some can be pretty lousy either in the performance aspect or the recording aspect—or both. But the right combination of soloist, conductor, and orchestra can be truly magical. Most of the recordings listed below are just that.

Note: when searching for the recordings, input the name of the conductor or soloist first and the orchestra next.

Opera overtures are the classical music version of speed dating as in several minutes, everyone gets excited, no one gets hurt, and then it’s over. For that reason alone Mozart’s overtures are easily the best introduction to his music. The Magic Flute and Marriage of Figaro are personal favorites. The latter can best be described as Champagne expressed in music.

2. String Quartets 20 in D Major and 21 in D Major, Alban Berg Quartet

Think chamber music and string quartets are light, boring, and fluffy? Think again. These two gems are beautifully played by the Alban Berg quartet from Vienna. The Champagne Mozart comparison definitely applies here as well.

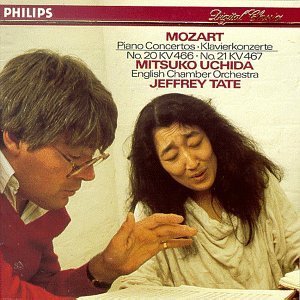

Mozart’s 27 piano concerti are my desert island tunes. I first studied them as an undergraduate and they get more play on my iTunes than practically anything else. Strange, but true. All are made up of three movements and last from 15-25 minutes, so they’re easily doable on the “are we there yet?” scale. Number 20 in d-minor is my favorite Mozart concerto of all. It’s driven, manic, melancholy, and triumphant in turn. Understand that Mozart wrote precious few things in a minor key, and when he did it was serious-ass business. Number 21 by contrast is like a beautiful summer night. Mitsuko Uchida is one of the great Mozart pianists of our age; her playing is perfection.

4. Piano Concertos 23 in A Major and 19 in F Major, Maurizio Pollini piano, Karl Böhm, Vienna Philharmonic

Amazingly precise and artistic playing by Italian Maurizio Pollini accompanied by one of world’s greatest orchestras and one of the top Mozart conductors of the 20th century. This is a wow.

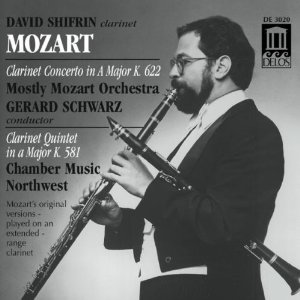

This is one of my favorite classical recordings of all time. Period. Buy it.

6. Symphonies 38 in D-Major “Prague”, 39 in E-flat Major, 40 in g-minor (that minor thing again) and 41 in C Major; Sir Charles Mackerras conducting, Prague Chamber Orchestra

There are 41 or 60 symphonies depending on whose catalogue you use. The early symphonies are short, charming, and not long on content or complexity. The late symphonies, nos. 35-41, are the sweet spot and responsible for Mozart being considered among the greatest symphonists of all time (think Beethoven, Mahler, Brahms and Hadyn). The coda of the last movement of Symphony no. 41 is stunning just for its brilliant counterpoint writing. Mackerras’ conducting and the Prague Chamber Orchestra is a great match.

7. Violin Concertos 1-6, Anne-Sophie Mutter violin, Yuri Bashmet conducting, London Philharmonic

Dazzling performances by German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. I also like the older recordings of Beglian violinist Arthur Grummiaux as well.

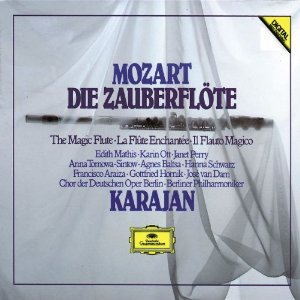

8. The Magic Flute, Herbert von Karajan conducting, Berlin Philharmonic

9.The Marriage of Figaro, Sir Charles Mackerras conducting, Scottish Chamber Orchestra

The last two recommendations are you having purchased/downloaded many of the above recordings and deciding to go the whole hog–as in opera. I’ll be the first to say that opera is not for everyone. Depending on how you think about it, opera is either the most artificial or the most dramatic and realistic form of music. I think it’s a little of both. Regardless, these two Mozart operas are arguably the best introduction to opera genre simply because of the purity and beauty of the music. In other words, there are a lot of great tunes in both works.

Cheers!

nn