“Whenever life begins to crush me I know I can rely on Bandol, garlic, and Mozart.”

Jim Harrison

Recently I reread Jim Harrison’s last book called “A Really Big Lunch.” If not familiar, Harrison was a prolific writer of poetry and prose, with works including the much-lauded trio of novellas called Legends of the Fall. He was also a raging gourmand with enormous appetites not unlike the fabled Gargantuan of Rabelaisian fame. I don’t make that statement lightly. Harrison was obsessed with good food and wine. He made no bones about drinking two bottles of Bandol rouge a day. Mind you he never bothered with conventional wine glasses instead opting for a huge tumbler and 12-ounce pours that he “gulped.”

What’s striking about revisiting the book is Harrison’s ADHD—which was significant. Reading his text is like being shoved into a cranial pinball machine and being smacked about with at least a half dozen topics on every page—all done with great elan and cleverness. To that point, Jim was an astute observer of the human condition and a brutal social critic. And he spared no one including himself.

Food and wine take center stage in the book. Throughout more than three dozen essays on topics varying from politics to the world going to hell in a hand basket, Harrison can’t resist the lure of what he calls “vivid” eating: hunting quail at his Arizona ranch, making bear posole at his cabin in Montana, and any number of ways of preparing tripe. There’s also no shortage of descriptions of dozens of meals enjoyed at high-end restaurants in France and beyond. The book’s centerpiece—and title essay—describes a certain lunch in 2003 at a French restaurant owned by Harrison’s favorite chef, Marc Meneau. In a marathon eight hour session (with breaks, of course), Harrison and eleven others including actor Gerard Depardieu dined on 37 courses washed down by over 15 legendary French wines, some dating back to the 1950s.

If you think 37 courses is the stuff of excess, you would be right. It’s hard to argue with that. It’s also hard to believe anyone was still alive the next day. This is French cooking after all, where using every possible source of fat is the norm and not an exception. Harrison also chronicles how he wandered around Paris for hours the day after in a food coma. But then he found himself peckish by dinner time needing to stop at one of his favorite bistros before boarding a red eye back to New York.

Harrison’s views on politics—and everything else for that matter—were strong water. No minced words, no middle ground. He hated the Bush administration vehemently, saying it drove him to eat, drink, and smoke to excess—which he already did. His opinions on wine were just as strong. To him, good wine had to be red—the color of blood.

“The great north from which I emerge demands a sanguine liquid. White snow calls out for red wine, not the white spritzers of lisping socialites, the same people who shun chicken thighs in favor of characterless breasts and ban smoking in taverns. In these days it is easy indeed to become fatigued with white people white houses, and white rental cars.”

No surprise that Jim was an acolyte of the wines from importer Kermit Lynch, the latter responsible for putting dozens of French wine appellations—many red—on the international map. Domaine Tempier, in particular, was an obsession with Harrison. White wines were a mere place holder in his universe, only to be tolerated if red wine was unavailable—or if a certain situation demanded it. Ultimately, he had to opt for white wine after being diagnosed with type two diabetes when “two bottles of red wine a day became inappropriate, a euphemism of course. One bottle a day is possible with a proper morning walk with the dogs, or rowing a drift boat for four hours in a fairly heavy current.”

Harrison is not the first I’ve come across who dismissed the white wine category outright. Over the years certain friends and acquaintances would eschew the white wine universe for various reasons, some vague and most arbitrary. The opposite could also be true. Some would profess not to be able to drink red wine because it gave them headaches. Of course they never connected the dots between over-indulgence and said headaches. However, the culprit behind the headaches could have been any number of things, including histamines and tannin in the wine to dehydration. Many times I suggested that someone take an antihistamine before slurping down that first glass of Merlot. Mind you there is always such a thing as too much wine.

In truth, everyone’s sensitivity—or lack thereof—to the structural elements in wine is different. Some crave white wines with insanely high levels of acidity, such that they could be used to make ceviche. Said acid freaks probably drank the vinaigrette remnants right out of the salad bowl as kids. Others like the monster truck pull experience from the tannins of a just-released Napa Cabernet. The same wine might cause another’s face to implode.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention context at this point. It trumps everything. A particular bottle sipped during a gorgeous sunset on a first date can become a married couple’s perennial favorite wine. Or any number of first wine experiences enjoyed while in an exotic location. Then there’s the guy who was a regular when I bartended at Bentley’s Seafood and Oyster Bar in the financial district in the City in the 80s. He always wore a pink cashmere sweater. And he drank nothing but White Zinfandel. He once told me that he didn’t care for the wine so much as he wanted to drink something that matched the color of his sweater. I should also mention that he added Sweet’N Low to his White Zinfandel.

I can’t imagine not drinking white wine. To me it’s a vital part of the vinous spectrum—the Yin to the Yang of red wine, the day to the night, the Abbott to Costello, etc. More often than not, white wines are a much more precise lens of a place compared to their red counterparts, in which high alcohol, tannin, and new oak can muddy things. In particular, I’m a fan of unoaked, high-acid, and mineral-driven European whites, from Sancerre to Chablis to Pinot Bianco to Assyrtiko. Riesling is a favorite. Spätlese Riesling from Germany is my sweet spot. Literally. I think Riesling is transcendent and transparent. It offers a pristine representation of a vineyard and its microclimate like few other wines. Certain Rieslings also tend to be lower in alcohol. Combined with high acidity, it makes them a chameleon with food, matching well with just about anything aside from red meat or live game.

Age also matters. Not wine age, but carbon-dating our own world-weary carcasses. Specifically, the higher alcohol levels, tannins, and histamines in red wines are harder to metabolize as we get older. Not to mention that red wines are usually accompanied by some form of protein at the table with fat and salt on the side. Less red meat over time usually means less red wine. Perhaps that’s not a bad thing. One can always make exceptions.

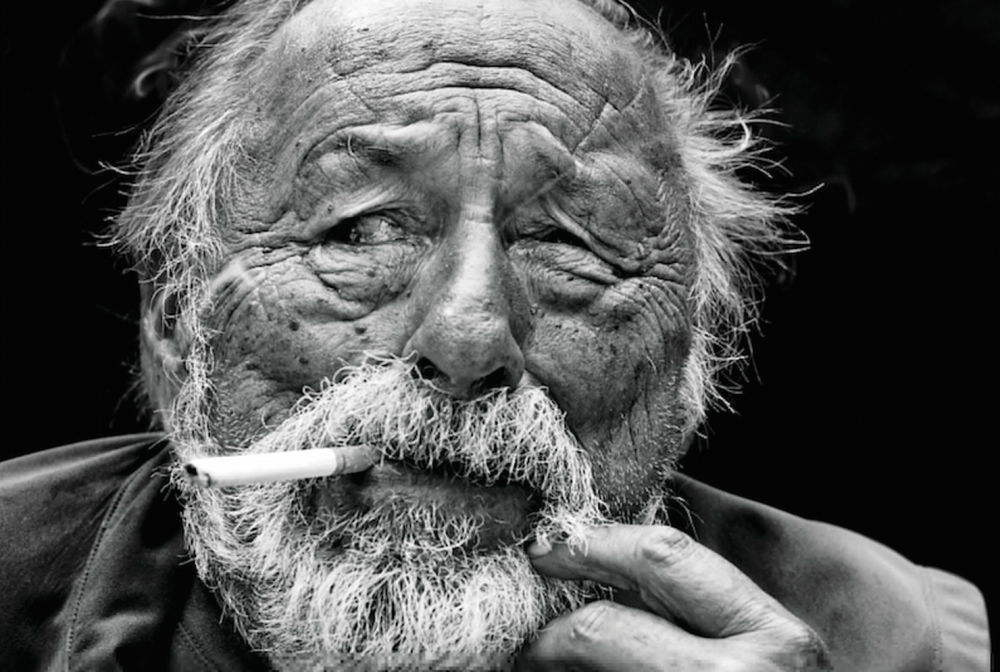

In the end, it’s often said that a picture is worth a thousand words. That’s definitely true with the image above. Harrison looks like pressed rat and warthog of 60s rock lyrics fame. The decades of hard living, chain smoking, and gargantuan eating and drinking eventually took their toll. First, diabetes and then several bouts of gout. In the end, he died of a heart attack on March 26, 2016, in Patagonia, Arizona, at age 78.

It makes me wonder about Harrison’s life and idea of “living vividly.” Is it better to play it safe than exit stage left at a younger age? I’m not sure, but there must be some sort of middle ground. Whatever it is, I’m pursuing it. And I’ll keep drinking white wine while I’m at it.

Jim Harrison

Recently I reread Jim Harrison’s last book called “A Really Big Lunch.” If not familiar, Harrison was a prolific writer of poetry and prose, with works including the much-lauded trio of novellas called Legends of the Fall. He was also a raging gourmand with enormous appetites not unlike the fabled Gargantuan of Rabelaisian fame. I don’t make that statement lightly. Harrison was obsessed with good food and wine. He made no bones about drinking two bottles of Bandol rouge a day. Mind you he never bothered with conventional wine glasses instead opting for a huge tumbler and 12-ounce pours that he “gulped.”

What’s striking about revisiting the book is Harrison’s ADHD—which was significant. Reading his text is like being shoved into a cranial pinball machine and being smacked about with at least a half dozen topics on every page—all done with great elan and cleverness. To that point, Jim was an astute observer of the human condition and a brutal social critic. And he spared no one including himself.

Food and wine take center stage in the book. Throughout more than three dozen essays on topics varying from politics to the world going to hell in a hand basket, Harrison can’t resist the lure of what he calls “vivid” eating: hunting quail at his Arizona ranch, making bear posole at his cabin in Montana, and any number of ways of preparing tripe. There’s also no shortage of descriptions of dozens of meals enjoyed at high-end restaurants in France and beyond. The book’s centerpiece—and title essay—describes a certain lunch in 2003 at a French restaurant owned by Harrison’s favorite chef, Marc Meneau. In a marathon eight hour session (with breaks, of course), Harrison and eleven others including actor Gerard Depardieu dined on 37 courses washed down by over 15 legendary French wines, some dating back to the 1950s.

If you think 37 courses is the stuff of excess, you would be right. It’s hard to argue with that. It’s also hard to believe anyone was still alive the next day. This is French cooking after all, where using every possible source of fat is the norm and not an exception. Harrison also chronicles how he wandered around Paris for hours the day after in a food coma. But then he found himself peckish by dinner time needing to stop at one of his favorite bistros before boarding a red eye back to New York.

Harrison’s views on politics—and everything else for that matter—were strong water. No minced words, no middle ground. He hated the Bush administration vehemently, saying it drove him to eat, drink, and smoke to excess—which he already did. His opinions on wine were just as strong. To him, good wine had to be red—the color of blood.

“The great north from which I emerge demands a sanguine liquid. White snow calls out for red wine, not the white spritzers of lisping socialites, the same people who shun chicken thighs in favor of characterless breasts and ban smoking in taverns. In these days it is easy indeed to become fatigued with white people white houses, and white rental cars.”

No surprise that Jim was an acolyte of the wines from importer Kermit Lynch, the latter responsible for putting dozens of French wine appellations—many red—on the international map. Domaine Tempier, in particular, was an obsession with Harrison. White wines were a mere place holder in his universe, only to be tolerated if red wine was unavailable—or if a certain situation demanded it. Ultimately, he had to opt for white wine after being diagnosed with type two diabetes when “two bottles of red wine a day became inappropriate, a euphemism of course. One bottle a day is possible with a proper morning walk with the dogs, or rowing a drift boat for four hours in a fairly heavy current.”

Harrison is not the first I’ve come across who dismissed the white wine category outright. Over the years certain friends and acquaintances would eschew the white wine universe for various reasons, some vague and most arbitrary. The opposite could also be true. Some would profess not to be able to drink red wine because it gave them headaches. Of course they never connected the dots between over-indulgence and said headaches. However, the culprit behind the headaches could have been any number of things, including histamines and tannin in the wine to dehydration. Many times I suggested that someone take an antihistamine before slurping down that first glass of Merlot. Mind you there is always such a thing as too much wine.

In truth, everyone’s sensitivity—or lack thereof—to the structural elements in wine is different. Some crave white wines with insanely high levels of acidity, such that they could be used to make ceviche. Said acid freaks probably drank the vinaigrette remnants right out of the salad bowl as kids. Others like the monster truck pull experience from the tannins of a just-released Napa Cabernet. The same wine might cause another’s face to implode.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention context at this point. It trumps everything. A particular bottle sipped during a gorgeous sunset on a first date can become a married couple’s perennial favorite wine. Or any number of first wine experiences enjoyed while in an exotic location. Then there’s the guy who was a regular when I bartended at Bentley’s Seafood and Oyster Bar in the financial district in the City in the 80s. He always wore a pink cashmere sweater. And he drank nothing but White Zinfandel. He once told me that he didn’t care for the wine so much as he wanted to drink something that matched the color of his sweater. I should also mention that he added Sweet’N Low to his White Zinfandel.

I can’t imagine not drinking white wine. To me it’s a vital part of the vinous spectrum—the Yin to the Yang of red wine, the day to the night, the Abbott to Costello, etc. More often than not, white wines are a much more precise lens of a place compared to their red counterparts, in which high alcohol, tannin, and new oak can muddy things. In particular, I’m a fan of unoaked, high-acid, and mineral-driven European whites, from Sancerre to Chablis to Pinot Bianco to Assyrtiko. Riesling is a favorite. Spätlese Riesling from Germany is my sweet spot. Literally. I think Riesling is transcendent and transparent. It offers a pristine representation of a vineyard and its microclimate like few other wines. Certain Rieslings also tend to be lower in alcohol. Combined with high acidity, it makes them a chameleon with food, matching well with just about anything aside from red meat or live game.

Age also matters. Not wine age, but carbon-dating our own world-weary carcasses. Specifically, the higher alcohol levels, tannins, and histamines in red wines are harder to metabolize as we get older. Not to mention that red wines are usually accompanied by some form of protein at the table with fat and salt on the side. Less red meat over time usually means less red wine. Perhaps that’s not a bad thing. One can always make exceptions.

In the end, it’s often said that a picture is worth a thousand words. That’s definitely true with the image above. Harrison looks like pressed rat and warthog of 60s rock lyrics fame. The decades of hard living, chain smoking, and gargantuan eating and drinking eventually took their toll. First, diabetes and then several bouts of gout. In the end, he died of a heart attack on March 26, 2016, in Patagonia, Arizona, at age 78.

It makes me wonder about Harrison’s life and idea of “living vividly.” Is it better to play it safe than exit stage left at a younger age? I’m not sure, but there must be some sort of middle ground. Whatever it is, I’m pursuing it. And I’ll keep drinking white wine while I’m at it.