n

Neuroscientists tell us that we have taste receptors on our tongues predicated to seven things: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, umami, kokumi (calcium) and fat. Sweetness is near and dear to us as children supposedly because of the sweetness we inherently crave in our mother’s milk. Bitterness is by far the last of the seven tastes for which we acquire a taste. That’s simply because bitterness is a biological trigger for anything poisonous or unhealthy in food and drink. Our natural response/aversion to something that tastes bitter probably goes back thousands of years when our major concern was remembering where we last saw the saber tooth tiger. Nowadays, it’s only with age and the onset of adulthood, whatever that is, that a fondness or even craving for all things bitter develops. Hence our love of coffee, espresso, radicchio, and digestifs such as amari. Many, however, will go throughout their entire lives with a hightened sensitivity to–and utter dread of–bitterness in food and drink. Ah, such sadness.

Enter Fernet Branca, the amaro extraordinaire. The original Fernet was the creation of Bernardino Branca and his three sons. It was first offered for commercial sale in 1845 and advertised as a healthy tonic for a variety of malaises. In its early days, Fernet was described as a “renown liqueur” that was “febrifuge, vermifuge, tonic, invigorating, warming and anti-choleric.” To the latter, the Branca family showed exceptional business acumen by having several local physicians officially validate their bitter elixir as a preventative and curative to cholera whose frequent outbreaks in the local region were a cause of great concern.

I first came across Fernet Branca over 25 years ago during my bartending days in San Francisco, thanks to good friend Michael Bugella. A few years later, Fernet saved my life socially (one might argue ecumenically as well) when it restored me from a monumental hangover and enabled me to stand in as best man at a good friend’s wedding. I have been a devotee ever since.

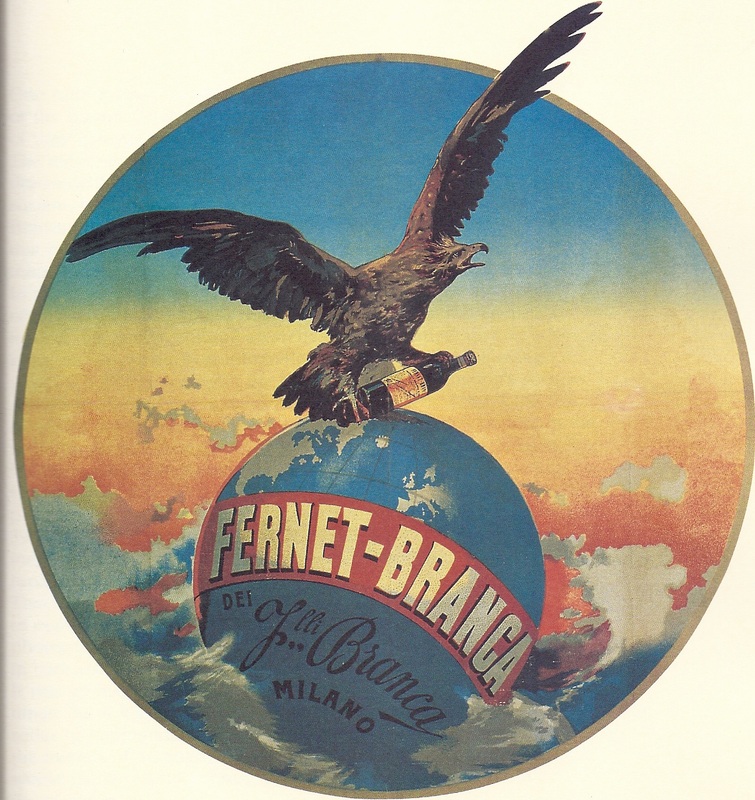

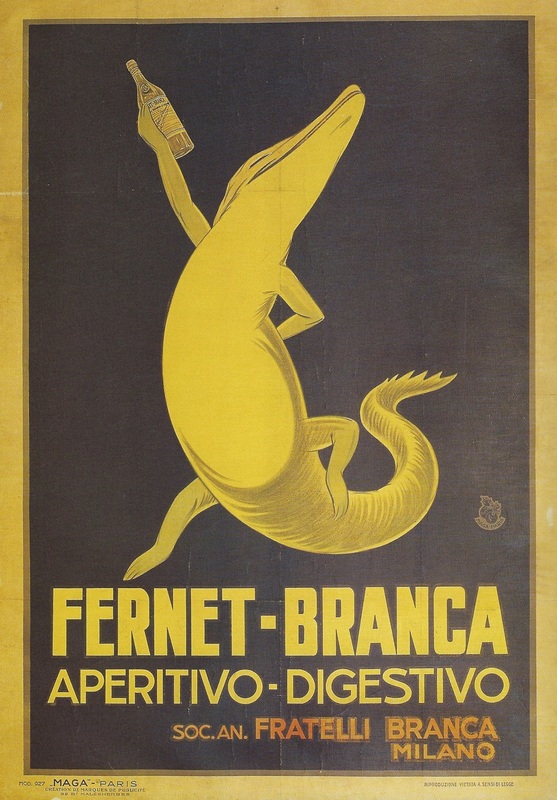

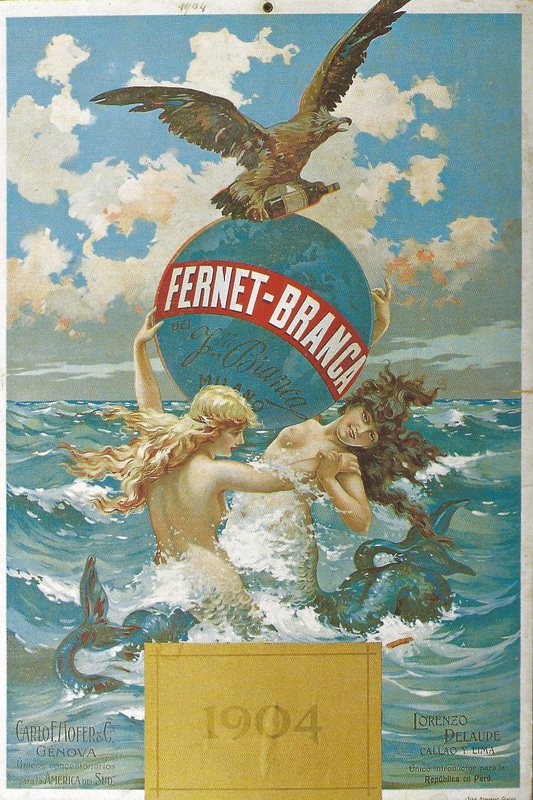

Fast forward to last week: I was in Italy visiting wineries and vineyards in Alto Adige, arguably the most unique of country’s 20 wine regions. One of the highlights of the trip was an extra day spent in Milan, specifically a tour of the Fernet Branca distillery. Fellow MS Geoff Kruth and I drove the three-plus hours from Bolzano to Milan early that morning to make our appointment. The distillery takes up an entire city block in an older industrial part of the city. Original photos and illustrations show it surrounded by farms and pastureland when first built. It’s now surrounded by urban sprawl and graffiti. Once there, Geoff and I were greeted by Marco, a fine young lad well versed in all things Fernet. He led us into the superbly appointed Fernet museum which was first opened in 1980. Its halls are filled with old presses, stills, production tools, photos, and memorabilia as well as the original artwork produced by the company over the last 150 years

I’ve heard forever and a day that the ingredients in Fernet were a top secret. Not true. Rounding a corner, we came upon a large raised circular display offering all the 27 active ingredients in Fernet. The list includes the likes of chamomile, myrrh (for bitterness!), star anise, grains of paradise, juniper, green coffee beans, cinchona bark, gentian, rhubarb, white agaric, linden, cocoa beans, mace, laurel leaf, bitter orange peel, orris, Colombo root, Zedoary, cardamom, Greater Galanga (whatever that is), cinnamon, marjoram, Musk Yarrow, tea leaves, small Centaury, aloe, saffron, and peppermint.

While the Branca team is more than happy to let the world know what ingredients are in its wonderful elixir, its actual production methods are indeed a trade secret. To point, Geoff, Marco, and I donned gauzy paper clean suits and strolled through the production area for Café Borghetti, the company’s delicious coffee liqueur. We also saw the enormous vat used for aging the Stravecchio Branca, the company’s brandy. But we were not allowed to see any the area used for distillation and production for both Fernet and Branca Menta. We were, however, taken into the sacred aging hall filled with hundreds of 1,000 liter wooden vats filled with Fernet quietly sleeping away for the required year to age and marry all the exotic components.

The tour ended with a stop at the Fernet reception bar in a large room filled posters and a burgundy colored Fernet Fiat sedan from the 1930’s complete with logos. Marco first poured tastes of the entire line of outstanding Carpano vermouths (acquired by the Branca family in 2001). The bitter Punt e Mes and the utterly delicious Antica are two of my favorite aperitifs. We also tasted the Stravecchio Branca (great value) and Café Borghetti.

Marco then pulled shots of Branca Menta out of the

Branca Brrrr machine, a small refrigerated unit resembling a snow cone maker. Menta was created in 1960 for the legendary opera soprano Maria Callas, who liked to drink her regular Fernet with mint. The family obliged by concocting the Branca Menta which is slightly sweet and intensely minty. We then capped off the tasting with a shot of Fernet which brought everything go a perfect close; it was ninety minutes of heaven.

From the very earliest days the Branca family’s maxim has always been Novare serbando—renew but conserve. I couldn’t have said it better. Salute!

nn