n

The lovely and brilliant Emily Prenkins was the kind of English teacher every kid dreams about. She was just a few years out of grad school and young enough to be able to speak meaningfully and empathetically to us students trapped in the pubescent hormonal wilderness, yet old enough to be able to share the wisdom of adulthood without all the baggage. During that first semester, Ms. Prenkins sought to bring out the creative voice in all of us. She coaxed clumsy poetry out of the lumbering football players who otherwise lorded over the back of the classroom. She pushed us to write short stories and to ponder the mysteries of Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine. Going to school may have been drudgery, but going to Ms. Prenkins’ English class at fifth period right after lunch was the highlight of any day.

However, there was a cloud on this sunny horizon in the form of Ms. Prenkins’ tummy, which gradually began to expand as the fall progressed. I have to say that if left to us boys to take notice it, would have come to our attention just before the birth of the child. Thankfully, the girls were quicker to pick up on it and soon whisperings of Ms. Prenkins “being with child” as they like to say in the good book filled the school halls. Thus it was no real surprise when she announced the week before Halloween that she was indeed pregnant. What was a surprise—more like a shock–was that she would be going out on maternity leave after Christmas break, and would be taking the entire second semester off. The class took it hard and for days after we, her devoted fifth period acolytes, were stunned. Ms. Prenkins did her best to console us and ushered us through the rest of the fall curriculum as best she could.

The holidays came and went with the usual December Albuquerque bitter cold, biting winds, and a dusting of snow. The Monday after New Year’s came too soon and with it the realization that the angelic face of Ms. Prenkins would be absent at fifth period. We filed into the classroom after lunch that Monday waiting for the substitute and hoping for the best but fearing the worst. Would the sub be some dotty spinster just this side of retirement or a hatched-faced disciplinarian hell bent on making all of us suffer for 55 minutes five days a week? We sat in nervous, expectant silence probably not unlike what Mr. Prenkins had gone through in the waiting room just days before (it was a girl).

Nothing could have prepared us for what, or who to be precise, came strolling through the door several minutes late. He—not she–was tall and lanky, wearing cowboy boots and sporting large, thick glasses. He had a receding hairline destined to arrive at a captain comb-over phase at some point in the future, and a large mustache groomed somewhere between a handlebar and Tucumcari. He breezily said good afternoon to us and then sat down heavily at the front desk, picking up the copy of our textbook and looking at it as if it was the first time. It probably was. He spent the next 5-10 minutes perusing its pages, snorting and mumbling now and then. Finally, he tossed it on the desk with a loud thud. “What a load of crap,” he proclaimed, with disdain for all and sundry to hear. “How do they expect you to learn anything from that?” We stared back with the expression of dazed livestock. “My name is Mr. Daniels,” he announced. “I’m your teacher this semester. Now I’ve heard all about Ms. Prenkins; in fact, I know her. She’s a wonderful teacher. But my style is different. I feel it’s my job to teach you English to the best of my ability and that has little to do with what’s in this book.”

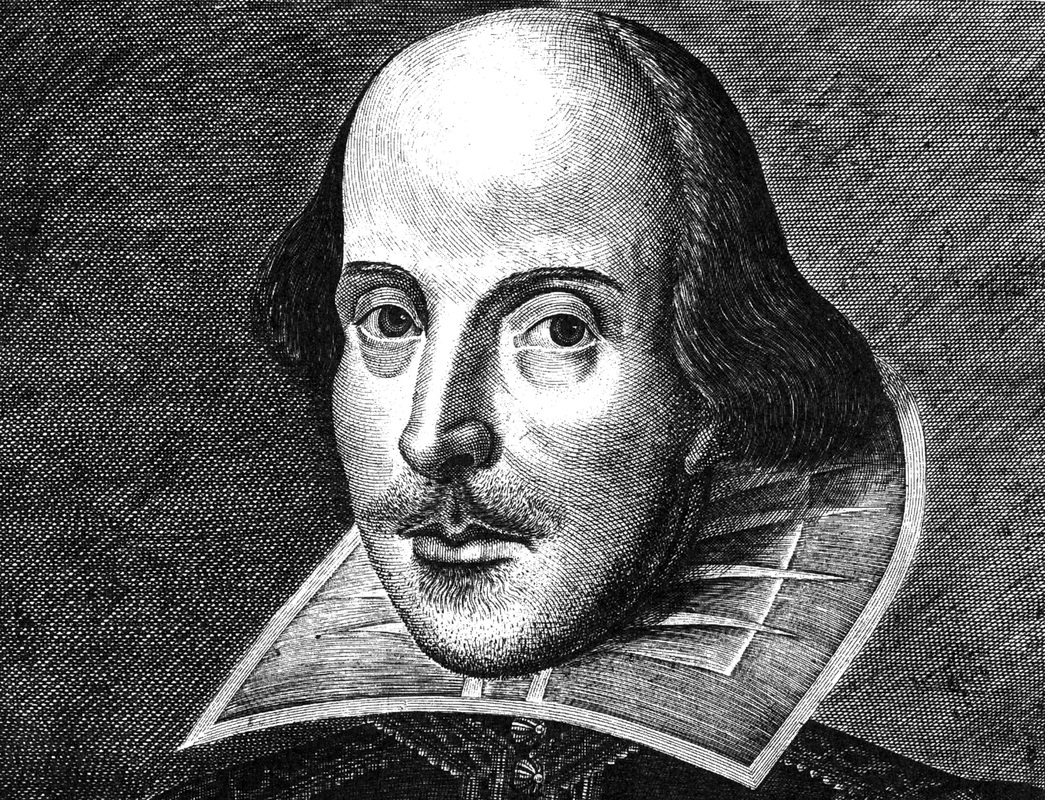

All of us shifted uneasily in our desks. Mr. Daniels suddenly seemed dangerous. There was no telling what he had planned. Visions of inquisition-like torture and caning filled my inner visage. But he soon remedied the mystery by announcing that we would all be learning English as a language that semester from the best source in civilized history—William Shakespeare. The collective groan from the class was immediate, involuntary, and more than audible. Mr. Daniels smiled in response. “I know what you’re thinking,” he said. “Shakespeare’s a dead guy. He’s been dead for over 400 years. What could he possibly have to teach us in the 20th century? The answer is a lot.”

Once the books were in our hands, he had us turn to Twelfth Night to Act II, scene V. Then Mr. Daniels stood up tall in front of the class and began to read from the scene with the projected, sonorous voice of an actor who had done plenty of time on stage. His voice had the menacing depth of Darth Vader combined with polished locution of a career politician. In mere seconds, we stopped reading along and stared agawk at him as he finished with Malvolio’s famous lines:

“In my stars I am above thee; but be not afraid of greatness: some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em.”

A vacuum of silence followed his reading of those lines. “That,” he announced, “is great English. By the end of the semester you’ll know more about the English language that probably most of your parents. You’ll know the ins and outs and the hows and whys we speak the way we do, because no one has ever written in the English language better than Shakespeare—and no one ever will. And all that starts today.”

Mr. Daniels then proceeded to take Malvolio’s famed lines apart, explaining how they revealed the comedic flaws of his character, how they fit into the overall plot of the play, and how they were relevant to life in Shakespeare’s time. He explained it all with the utmost simplicity so it was easy to understand and yet with great intensity and urgency, as if to say all of this stuff really mattered and we had better pay attention. We did so in rapt silence.

Next Mr. Daniels outlined his vision for the semester. If we agreed to his plan, we would follow the rules of the “establishment” as required by covering various parts of the text book. We would also have intermittent quizzes on said material. But the bulk of the class time would be spent on learning scenes from Shakespeare and–get this—actually acting them out. That last bit proved the tipping point and suddenly our collective angst, frustration, and fear bubbled up and all over the linoleum floor in a messy goo.

“We can’t do that!”

Shakespeare is soooo boring!

“This is STUPID!”

“You can’t make me do that.”

“I’m telling my parents.”

“I can’t memorize anything!”

“I’m afraid of talking in front of other people.”

Through the firestorm of protest, Mr. Daniels simply smiled and nodded as if he was truly enjoying our reaction. When the ruckus died down he said, “I know, I know. I’ve heard it all before. But if we don’t do something different to learn English this class will be just as useless as practically every other class you’ve ever had. And I’m not going to be part of that.”

Mr. Daniels spent the rest of that first day talking about life in London during Shakespeare’s time; how filthy, downtrodden, and incredibly difficult it was with the average life expectancy less than 18 years; how most people lived a desperate existence filled with poverty, hunger, and disease. Among this squalor and suffering, were the theaters where anyone could take respite from their bleak life for a few moments to be entertained with news of the day as well as comedy, drama, singing, and dancing. He went on to explain some of the conventions of language of the time, the witticisms, and the references to events of the day as well as Greek and Roman mythology–and he did it all in his drawling easy-to-understand way. It was like getting a crash course from your next door neighbor’s dad on the history, politics, and sociology of Elizabethan England—in less 30 minutes. And that was just day one.

The group next to us had been assigned Romeo and Juliet, and there, towering over everyone even when sitting down, was Glen Turner. Glen was really tall with the physique of a human tongue depressor. He was a shy lad and routinely did everything within his power to be invisible, which was impossible given the fact that he was at least six inches taller than the rest of us. But that day Glen was utterly inconsolable. He had just landed the part of Romeo in the balcony scene and the part of Juliet would be played by Grace Ann Warren–one of the cutest girls in the entire school.

The following day the four troupes started to work through their assigned scenes. Mr. Daniels would first help by reading through some of the text to explain the language, and then coach us, the “players,” on how to say our lines. From there, we would work on the parts, script out the scenes, and try to figure out what props we needed to make them work. All the while, Mr. Daniels went from group to group watching and coaching, always praising and never criticizing anyone unless they weren’t trying. He was especially attentive to Glen Turner, who threatened to implode at any moment.

In the days and weeks to come, Mr. Daniels really got into his element. He pushed, soothed, and threatened; he pleaded, wheedled, and cajoled, forcing any and every one uttering a line in front of the rest of the class to not screw around and to really go for it. I have to say that when it was my turn to play the part of the ever-mischievous Sir Toby, I thought I might soil myself at the prospect of saying my lines in front of the rest of the class. But after some initial faltering and Mr. Daniels’ prompting and encouragement, I found my squeaky teen voice and began to get into the part. The other kids did likewise, even the oft-traumatized Glen Turner though he took longer than most.

Once we were past that initial set of scenes, Mr. Daniels had to start telling everyone to tone it down and not be so “danged melodramatic” as he put it. Despite our best efforts to over-act at every opportunity, it was easy to see that he was delighted. At his suggestion, we began to fashion our own rough costumes and bring things from home to use as props. “Be creative!” he urged and one day when a kid in the class showed up with a shopping cart “borrowed” from a local supermarket he was simply giddy. Sword fights were enacted with gusto complete with plastic swords and cardboard lances. The girls started to get into the costume aspect of it all and a competition of sorts began to see who could design the laciest, frilliest maiden get up of all.

Needless to say, we were hooked. Beyond that, we totally got Shakespeare. The plays and the language became as real for us as anything we could possibly watch on TV. We got how a feud like the one between the Montagues and the Capulets could become unthinkably destructive. We learned how an individual in power like Richard III could be utterly evil and destroy everyone around them for their own ends. We also learned how love could be incredibly fickle from the crazy relationship between Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing. As time went on, there was less and less of the textbook and quizzes, and our memories of the fall semester with Ms. Prenkins also began to fade with sword fights, heroic deeds, and swooning maidens taking their place.

I’d like to say that the semester ended in a triumph like the movie, School of Rock, with our class staging a spirited performance of The Tempest in front of a live audience. That’s far from true. Just before spring break, the administration caught wind of Mr. Daniel’s “studio.” After the break we came back to fifth period all set to work on new scenes only to find a large, aging spinster sitting behind the desk. She waited for us to file in and once all were seated she announced in a withering tone that she was the new substitute teacher and that Mr. Daniels had been “reassigned.” We squawked loudly in protest but Mrs. Cranky Pants, who looked like a former professional wrestler, would have none of it. “Open your textbooks,” she barked. We meekly complied, our youthful thespian spirits quashed.

Mr. Daniels was never seen or heard from again. Rumors flew back and forth on whether he had been fired or had quit in dramatic fashion. We conjectured that he moved on to “infiltrate” other schools and classes in the much same way as ours, but no one could ever confirm that for a fact. Regardless, his spirit lives on. I’m reminded of him from time to time when I teach a class or make a presentation to a group. He taught me to care—desperately—about my students and to do whatever it takes make sure they get what I’m teaching. He showed me how to coach and how to constructively criticize. He was also the first to teach me how to stand up in front of group and deliver the goods when it’s on the line. Most importantly, he gave me a love of Shakespeare that continues to this day. If I could only take one book to that proverbial desert isle, it would be an easy choice—a copy of the complete works. And I would be a happy man.

nn