n

Tasting is the heart and soul of what we do as wine professionals. It’s both the “work” we do and also the most enjoyable thing about our profession. Any career in wine—whatever facet—ultimately comes down to tasting. After 25-plus years and tasting tens of thousands of wines I will submit that tasting has given me a wealth of knowledge. But there are many things you might not expect.

I would argue that beyond a certain point many of the benefits of becoming a professional taster have little to do with wine. They have everything to do with changing how we perceive the world. Sometimes the changes are subtle, other times profound. How has my tasting evolved since passing the exam over 20 years ago? Good question. Further, what has tasting taught me about myself that I wouldn’t have learned through other avenues? And what have I learned through tasting that has nothing to do with wine? Are there things beyond grapes and places in a glass?

Perhaps the most profound thing tasting has taught me is how I think; literally the sequence of how I internally process sensory information. Until I worked with behavioral scientist Tim Hallbom on camera in late 2009 I had no clue about how I processed olfactory and taste internally. Through his tracking my eye movements and language patterns we were able to deconstruct my internal tasting strategy. The result is that now I am vividly aware of how I perceive and organize sensory information from a glass of wine, and most importantly that smell and taste memory are an intensely visual experience internally. Without Tim’s help this wouldn’t have been possible. Trying to be aware of how you think about something while you’re thinking about it is like asking someone to be in two places at once. It’s like the Fire Sign Theater quote, “How can you be in two places at once when you’re really nowhere at all?” To be aware of how you think is an amazing gift; it maps over to all parts of your life. I use the strategies I learned in those two film sessions every day in a multitude of different ways.

Tasting teaches us how we think. It reveals in layers of smell and taste how we perceive and experience the world. In an age where mindfulness has become such a precious commodity, tasting also teaches us how to still the mind and shut the world out. Through practice we’re able to build ferocious yet gentle levels of concentration.

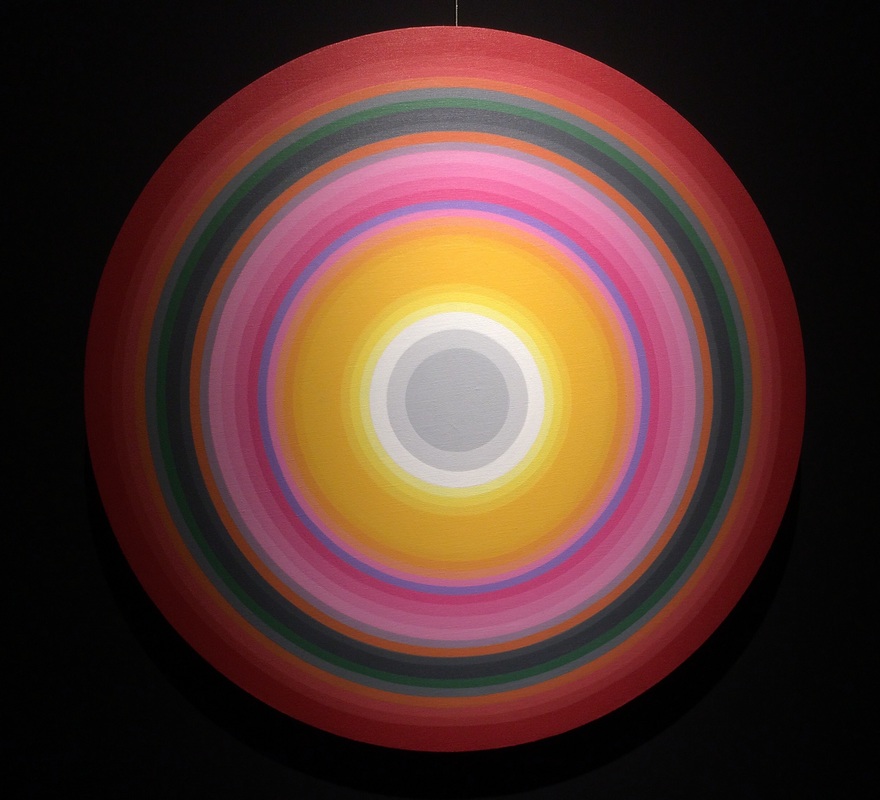

The intense focus of smelling and tasting wine is multi-layered; we alternate between going into the glass to “see” what’s there and then back again into our head to remember, calibrate, and assess what we’ve experienced. But we’re alternating between outside and inside so quickly that we’re usually not even aware of the change. At some point with enough experience and repetition we literally find ourselves between the two states, holding both at the same time in our field of awareness. I can only describe it as a tasting “trance.” There are eye positions that correspond to all three places as well as a soft, slightly unfocused quality to our gaze.

Tasting with a grid teaches us the discipline of memorizing and using a complex sequence for the sake of consistency. The MS deductive tasting grid has some 43 possible criteria that must be assessed in a given wine. Memorizing the grid is a considerable challenge but absolutely necessary for the student to have any consistency in their tasting much less success in classes and exams. Through repetition we’re eventually able to take this very complex conscious process involving multiple senses to the unconscious level.

Tasting teaches us how to calibrate sensory impressions precisely—as in the levels of alcohol, acid, and tannin in a given wine. Surprisingly, we do so with internal visual cues.

Tasting shows us how to keep a multitude of sensory information in our field of awareness–and how to be aware of all this information either in rapid sequence or simultaneously. To do so we create complex internal wine “maps” that allow us to keep all the sensory information in the glass organized in an orderly fashion so that it doesn’t go away and we can easily retrieve it for the sake of comparison or simply to review and remember it.

Teaching tasting to consumers or professionals teaches us how to communicate about a complex process and to chunk it down so it can be easily understood.

I would argue that beyond a certain point many of the benefits of becoming a professional taster have little to do with wine. They have everything to do with changing how we perceive the world. Sometimes the changes are subtle, other times profound. How has my tasting evolved since passing the exam over 20 years ago? Good question. Further, what has tasting taught me about myself that I wouldn’t have learned through other avenues? And what have I learned through tasting that has nothing to do with wine? Are there things beyond grapes and places in a glass?

Perhaps the most profound thing tasting has taught me is how I think; literally the sequence of how I internally process sensory information. Until I worked with behavioral scientist Tim Hallbom on camera in late 2009 I had no clue about how I processed olfactory and taste internally. Through his tracking my eye movements and language patterns we were able to deconstruct my internal tasting strategy. The result is that now I am vividly aware of how I perceive and organize sensory information from a glass of wine, and most importantly that smell and taste memory are an intensely visual experience internally. Without Tim’s help this wouldn’t have been possible. Trying to be aware of how you think about something while you’re thinking about it is like asking someone to be in two places at once. It’s like the Fire Sign Theater quote, “How can you be in two places at once when you’re really nowhere at all?” To be aware of how you think is an amazing gift; it maps over to all parts of your life. I use the strategies I learned in those two film sessions every day in a multitude of different ways.

Tasting teaches us how we think. It reveals in layers of smell and taste how we perceive and experience the world. In an age where mindfulness has become such a precious commodity, tasting also teaches us how to still the mind and shut the world out. Through practice we’re able to build ferocious yet gentle levels of concentration.

The intense focus of smelling and tasting wine is multi-layered; we alternate between going into the glass to “see” what’s there and then back again into our head to remember, calibrate, and assess what we’ve experienced. But we’re alternating between outside and inside so quickly that we’re usually not even aware of the change. At some point with enough experience and repetition we literally find ourselves between the two states, holding both at the same time in our field of awareness. I can only describe it as a tasting “trance.” There are eye positions that correspond to all three places as well as a soft, slightly unfocused quality to our gaze.

Tasting with a grid teaches us the discipline of memorizing and using a complex sequence for the sake of consistency. The MS deductive tasting grid has some 43 possible criteria that must be assessed in a given wine. Memorizing the grid is a considerable challenge but absolutely necessary for the student to have any consistency in their tasting much less success in classes and exams. Through repetition we’re eventually able to take this very complex conscious process involving multiple senses to the unconscious level.

Tasting teaches us how to calibrate sensory impressions precisely—as in the levels of alcohol, acid, and tannin in a given wine. Surprisingly, we do so with internal visual cues.

Tasting shows us how to keep a multitude of sensory information in our field of awareness–and how to be aware of all this information either in rapid sequence or simultaneously. To do so we create complex internal wine “maps” that allow us to keep all the sensory information in the glass organized in an orderly fashion so that it doesn’t go away and we can easily retrieve it for the sake of comparison or simply to review and remember it.

Teaching tasting to consumers or professionals teaches us how to communicate about a complex process and to chunk it down so it can be easily understood.

Blind Tasting

I played the trumpet from the time I was in fourth grade until the end of 1988 when I played my last rehearsal as an extra with the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. For me blind tasting is entirely too similar to the trumpet, which is arguably the most frustrating instrument there is to play. Why is the trumpet so frustrating? Simply because the vibrating medium that produces sound is part of your body meaning that your playing, however good you are, will vary from day to day depending on how good you physically feel—or not. One can be an outstanding trumpet player but completely suck on a given day. I’ve seen big name trumpet players take a dive. It’s not pretty. I’ve also been there myself having utterly tragic days where I shouldn’t have taken the horn out of the case.

Blind tasting is exactly the same; it’s humbling. Our “equipment” is our physical body and therefore variable and at times fallible. Blind tasting practice is a day to day process, trusting your body and your senses but knowing that on certain days you will be under par. It’s all about accepting mistakes, learning from them as quickly as possible, and then moving on. It’s also about raising the bar every time you taste so that on a given day at a given time you have more than enough to get over the required score in an exam. That was my approach to taking trumpet auditions and it was my approach to taking the tasting exams as well.

No surprise that trumpet auditions and tasting exams both taught me to focus under pressure. If anything, having taken auditions as a student and a professional were an advantage for me when I took the exams. Both taught me how to give my nervous system a choice between “flight” or “fight.” The auditions, for the record, were far more stressful.

Is one ever a great taster? I’m not sure. For me the belief of being a “great taster” is simply not useful. Adopt that belief and the universe will be all too happy to quickly show you someone who’s a better taster than you are. Count on it. My belief about my tasting is that I’m exceptionally good at analyzing and assessing wine. For me that’s a much more useful belief; it’s open ended and definitely win-win. Perhaps one isn’t a good or a great taster. One is always in the process—or on a journey—to become a better, more proficient taster.

Beyond the Work

Beyond the focus and repetition required to become a professional taster there are a multitude of things tasting teaches us if we allow it. First, that wine is the great connector; it connects us to people, cultures, history, and different geographical points on the globe. The ritual of sharing wine with friends or family is over 4,000 years old; with wine we’re able to connect with other people in a meaningful way not often found otherwise. Through wine we’re also able to experience a unique appreciation—even gratitude–for a product of the earth and the seasons. Certain wines allow us to experience a connection to places that have produced wine for centuries—even millennia. In a certain context these ancient wine places might be considered sacred spaces.

In the End

Scientists tell me that my sense of smell will start to diminish now because I’m getting older. Their assumption doesn’t take neuroplasticity into account or the mechanics of memory. My memory for wines and aromatics has never been better.

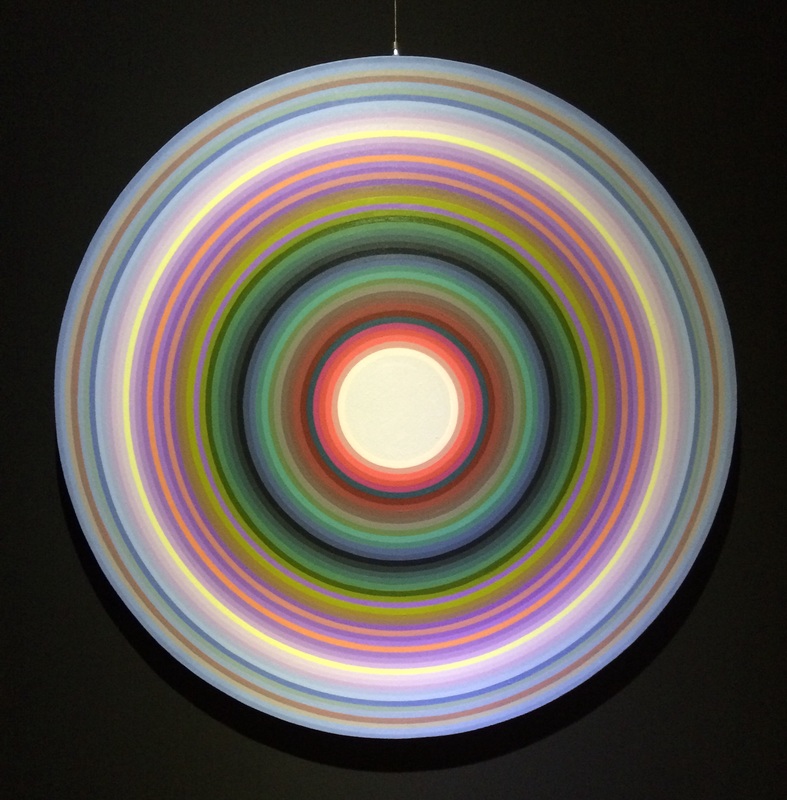

How will my tasting change in the future? A better question to pose might be, how will tasting change me in the future? If anything tasting—especially the olfactory part–will become more synesthetic for me as time goes on. I fully expect the feeling part of reacting to aromatics in a glass of wine to become more profound. My tasting trance, if anything, will become easier to access and deeper.

I’m looking forward to it.

I played the trumpet from the time I was in fourth grade until the end of 1988 when I played my last rehearsal as an extra with the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. For me blind tasting is entirely too similar to the trumpet, which is arguably the most frustrating instrument there is to play. Why is the trumpet so frustrating? Simply because the vibrating medium that produces sound is part of your body meaning that your playing, however good you are, will vary from day to day depending on how good you physically feel—or not. One can be an outstanding trumpet player but completely suck on a given day. I’ve seen big name trumpet players take a dive. It’s not pretty. I’ve also been there myself having utterly tragic days where I shouldn’t have taken the horn out of the case.

Blind tasting is exactly the same; it’s humbling. Our “equipment” is our physical body and therefore variable and at times fallible. Blind tasting practice is a day to day process, trusting your body and your senses but knowing that on certain days you will be under par. It’s all about accepting mistakes, learning from them as quickly as possible, and then moving on. It’s also about raising the bar every time you taste so that on a given day at a given time you have more than enough to get over the required score in an exam. That was my approach to taking trumpet auditions and it was my approach to taking the tasting exams as well.

No surprise that trumpet auditions and tasting exams both taught me to focus under pressure. If anything, having taken auditions as a student and a professional were an advantage for me when I took the exams. Both taught me how to give my nervous system a choice between “flight” or “fight.” The auditions, for the record, were far more stressful.

Is one ever a great taster? I’m not sure. For me the belief of being a “great taster” is simply not useful. Adopt that belief and the universe will be all too happy to quickly show you someone who’s a better taster than you are. Count on it. My belief about my tasting is that I’m exceptionally good at analyzing and assessing wine. For me that’s a much more useful belief; it’s open ended and definitely win-win. Perhaps one isn’t a good or a great taster. One is always in the process—or on a journey—to become a better, more proficient taster.

Beyond the Work

Beyond the focus and repetition required to become a professional taster there are a multitude of things tasting teaches us if we allow it. First, that wine is the great connector; it connects us to people, cultures, history, and different geographical points on the globe. The ritual of sharing wine with friends or family is over 4,000 years old; with wine we’re able to connect with other people in a meaningful way not often found otherwise. Through wine we’re also able to experience a unique appreciation—even gratitude–for a product of the earth and the seasons. Certain wines allow us to experience a connection to places that have produced wine for centuries—even millennia. In a certain context these ancient wine places might be considered sacred spaces.

In the End

Scientists tell me that my sense of smell will start to diminish now because I’m getting older. Their assumption doesn’t take neuroplasticity into account or the mechanics of memory. My memory for wines and aromatics has never been better.

How will my tasting change in the future? A better question to pose might be, how will tasting change me in the future? If anything tasting—especially the olfactory part–will become more synesthetic for me as time goes on. I fully expect the feeling part of reacting to aromatics in a glass of wine to become more profound. My tasting trance, if anything, will become easier to access and deeper.

I’m looking forward to it.

nn