n

Several days later he returned the CD saying, “I tried listening to it several times but just didn’t get it. I couldn’t find any tunes in it and the music really doesn’t make sense at all.” I told him no problem and thanked him for at least checking it out. In the next few days I thought about his reaction. Here was someone who constantly listened to a broad range of music—and quite a lot of classical music at that. Even with his profound love of music, the Bartok was an alien experience that failed to click with him. Why? Perhaps the answer was simply not enough time or experience listening to similar music.

Classical music strives to put on a friendly face to appeal to the masses. One can listen to a hopefully decent rendition of the Pachelbel Canon (which I fondly refer to as the “Taco Bell” Canon) at a niece’s wedding and sigh with contentment as the lilting sounds fill the nuptial space. But classical music can just as easily take a deep dive into complex depths that defy humming or random toe tapping. Here is where the Bartok resides, at the deep end of the pool. And it doesn’t take lightly to someone enthusiastically leaping in wearing water wings or other cute inflatable devices.

The point I make here is that despite the Taco Bell Cannon and other Reddy Whip tunes, what we call classical music is NOT easy. As a field, it covers a vast territory including the likes of history, culture, science, performance, psychology, and much more. The potential to spend an entire career much less an entire lifetime in study or performance exists in multiple arenas. Any real knowledge requires a journey involving a lengthy duration of time, focus, and a hell of a lot of work. But it can also be enjoyed by just about anyone just about any time.

The same holds true for wine.

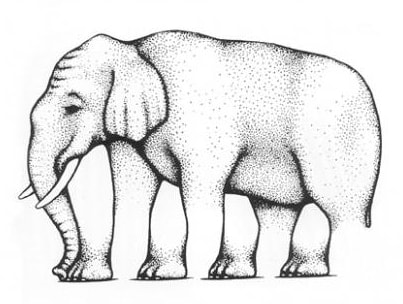

The Grand Illusion

Anyone who wants a glass of wine can usually obtain a bottle of mass-produced commercial plonk and be perfectly happy in the moment. A collector or industry professional can likewise open and pour a rare, uber-expensive bottle from a world-famous estate. Repeated sips of said nectar can and often do bring the partaker into a highly altered state that is impossible for them to describe—and equally impossible for practically anyone else to understand.

What’s the take away here? First, that context, as always, is the most important piece in the wine equation. Second, like classical music, wine is not easy. It can be as simple as Hearty Burgundy or as profound as a rare bottling of actual domain-bottled Burgundy.

We as an industry have long been guilty of putting up the grand illusion to the masses that wine is easy. That with a sip here and there and a quick read about the new vintage accompanied by those handy scores, one can “hack” being a wine expert. After all, what could someone who’s been in the business for a couple of decades possibly know that I don’t? Yes, we’ve lied long and often to the masses and it’s gotten us in trouble.

How then should we as an industry proceed? What can we do to provide a clear, well-lit path for those just getting into wine that will consistently provide the right information and experiences, even to the extent of showing the way to become a professional? Perhaps the answer to this dilemma is some kind of road map that lists frequent stops to define basic terms, give tasting tips, and provide easy to understand information about labels, styles, grapes, and places. But the map would also suggest a sequence of learning to make the process easy to track for anyone not just interested in a glass of wine—but a possible career. Until someone actually creates such a map, I will humbly offer some advice to those just getting into wine. But first, some useful guidelines to keep in mind before hitting the road.

A Few Apparent Wine Truisms

Other than the fact that it’s a liquid fermented from grape juice, there are precious few absolutes about fine wine. If you entertain the notion of proclaiming a new one to the masses, the universe will be all too happy to shove one or multiple exceptions in your face–immediately. However, there are a few truisms that seem to be accurate, at least most of the time. If you’re new to the wine game, these will help.

- Different people like different kinds of wines.

- One’s personal wine preferences have a lot to do with individual sensitivity and/or preference to what are called structural elements in wine: the levels of dryness-sweetness, acidity, and tannin.

- It’s quite possible to come across a wine that you strongly dislike, but that’s true to type and perfectly well made.

- Tasting wine is a combination of objective and subjective experience.

- In the beginning, tasting will seem like a completely subjective experience.

- Over time it will become more objective.

- Tasting is almost completely objective to an experienced professional.

- In other words, an established industry professional is not making things up when they talk about or write about wine. Seriously. If you think they do, you need to get a clue. Sorry, a bit of rant here but it needs to be said.

- Your palate—and the kinds of wine you like to drink–will change over time. Count on it.

- Context, as previously mentioned, is the single most important piece in the wine tasting equation. The who, what, when, where, and how you taste or drink a wine can be more important to the tasting experience than the wine itself.

- Finally, wine is not easy. But if you chip away at it—as in tasting, drinking moderately, and doing a bit of reading on a consistent basis, you can learn a lot about it over time and even master it after a great deal of time.

Someone once said that it takes a village to nuke a whale. Actually, I just made that up. Here is some sage advice I wish I would have had way back, when I first discovered wine.

Learn the basics: you’ll need a good reliable source of basic information. There are lots of books and websites out there, but for my money Winefolly.com and their book, Wine Folly: Essential Guide, is the best for anyone just getting into wine. Former student Madeline Puckette and her team have created brilliant graphics that really help wine click for the beginner.

Good glassware: decent glassware is a must (sorry about the wine pun). That said, avoid buying a zillion kinds of different glasses for each grape variety or laying out the big bucks for the hand-blown crystal behemoths that will break if you even look at them. One glass in the beginning will cover most of your wine needs—the Riedel Vinum Zinfandel/Sangiovese glass. It is the perfect tasting/drinking glass. As you move on, you’ll want to add the Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Champagne glasses, also from Riedel’s Vinum line.

Get a Coravin: there are lots of wine accessories on the market. Most are useless, if not utter crap, or have a very limited function. The exception is the Coravin, easily the most brilliant wine accessory ever invented. Using a surgical-quality needle and a small cannister of argon gas, the Coravin allows you to tap into any bottle and take out as much wine as desired leaving the rest preserved for months. In short, it allows the student (or anyone else) to taste a wine repeatedly over time without compromising the rest of the contents in the bottle. The Coravin is the one thing I wished I would have had when studying for exams eons ago. It would have saved me thousands of dollars in wine purchases for tasting practice.

Start a cellar: at some point you may be vinous-afflicted to the extent of buying more wine that you can possibly drink, at least in the near term. It happens. Know that there are lots of good sources on starting a cellar. Whether you dedicate a closet in your apartment or build a pricey shrine with fancy redwood racking, you absolutely must maintain the right conditions for the proper storage of wine: a constant temperature of between 55 and 60 degrees without any source of light or vibration. If you don’t, nature, as always, will bat last and your precious bottles will either age prematurely or completely oxidize. One further bit of practical advice: balance is key. If you do start a cellar, don’t fill it with collectible wine that needs to be aged or you’ll find yourself with nothing on hand to drink. Make sure at least 60% of the wine in your cellar is destined for early to mid-term enjoyment. You’ll thank me for that one.

Keep track of what you taste and drink: at the very least, use your phone to take photos of labels. It’s a good start. You can also take notes on your phone, your iPad, or—god forbid—actually write notes in a notebook. What a concept. An excellent tasting note template can be found in my last blog post (www.timgaiser.com/blog/on-tasting-notes).

Training: classes are good! Anyone can take the Master Sommelier Introductory Course. It’s two days of information-filled, fast-paced fun. I highly recommend it. However, beyond the Intro Course, the MS curriculum is geared specifically for those in the restaurant-hospitality industry—no matter how cool you think the sommelier thing is. If you’re not working on the restaurant floor, you should consider the WSET—the Wine and Spirits Education Trust. It’s an outstanding curriculum that’s available to anyone and some of the classes are available online.

Get in a tasting group: get into (or form) a tasting group. Working regularly with a group—even if it’s not formal–can really help improve your tasting skills. And if you don’t get overly nerdy serious about it, you can also have fun.

Find a good local retailer: the right retailer can be a valuable guide. They will quickly learn your palate, so to speak, and help steer you to wines that you will probably like. Equally valuable, they can also suggest new wines you wouldn’t necessarily know about much less try. Above all, a good retailer acts as a filter and will only recommend wines they can guarantee thereby saving you a great deal of time and money.

Good online resources: once past the basics, I recommend the following for keeping up with the ever-changing world of wine: www.guildsomm.com, www.decanter.com, www.wineanorak.com, and www.jancisrobinson.com.

Travel: as you delve deeper into the wine universe, trips to wine places are wonderful. There is no replacing tasting—and drinking—wines in their place of origin. That especially goes for the likes of German Riesling, Burgundy, and Sherry.

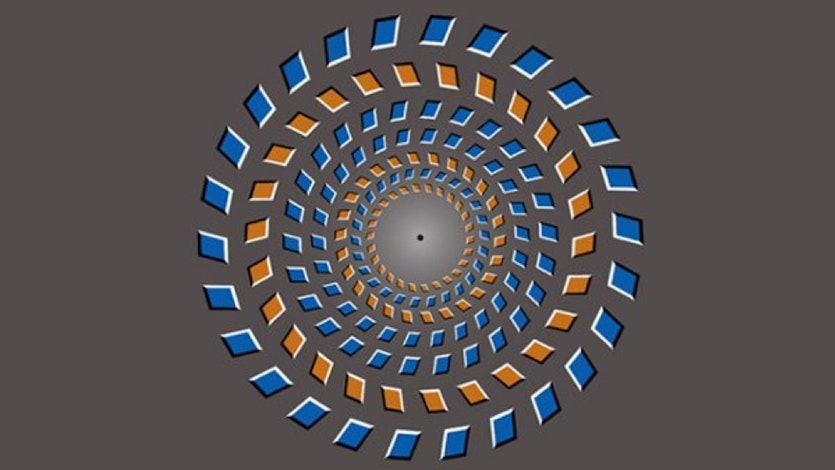

Numerical scores: take any publications that use numerical scores with at least a grain of salt. Numbers, specifically the 100-point scoring system, presuppose a precision in wine that has never existed–and never will. I think the 100-point system is the wine industry’s true unicorn. It’s a delightful hallucination that’s been around for so long and used by so many people that everyone thinks it’s actually real. Sound familiar? I must again remind you once again that wine is NOT easy. To think that a number can convey meaning in the context of tasting a wine is nothing short of fantasy.

Coda

Have patience when starting down the wine path. Prepare to be educated—and for the education to take some time. Try to avoid becoming compulsive about the whole thing. It will only annoy everyone in your life and might affect your socialization. Is the journey worth it? Absolutely! For god’s sake, this is not widgets we’re talking about. It’s wine, one of mankind’s greatest achievements. There is nothing better than sharing a glass of vino and a meal with friends and family. It’s one of the greatest gifts we have.

Cheers!

nn