n

Over 60 kinds of synesthesia have been documented. Some of the more common forms include grapheme, or color synesthesia, where letters or numbers are perceived as colors; ordinal linquistic personification, where numbers, days of the week, and months of the year are experienced as personalities; and spatial-sequence, or number form synesthesia, where numbers, months of the year, and/or days of the week are experienced as specific and very precise locations in space.

In thinking about Tammet, it’s tempting to put forth the idea that everyone experiences synesthesia from time to time given that our inner senses are so interdependent. Any strong memory–be it pleasant or not—is a complex package of intensely interconnected images, sounds, and feelings. But true neurological synesthesia is always involuntary thus differentiating individuals who experience it from the rest of us.

In regards to tasting and synesthesia, I’ve learned that most of the colleagues I’ve worked with in my tasting project are like me. We’re visual-dominant in our thinking and represent our internal experience of wine primarily with images in any number of different ways. However, over the last year I noticed several outliers among colleagues I’ve interviewed; professionals who taste at a world-class level but whose inner processing of the wine experience is so far outside the norm that their tasting strategies are challenging to deconstruct and code. To these few, the wine experience is not so much about using images associated with memories of aromatics and flavors, but instead experiencing wine as a flow, shape, colors, texture, and sounds often projected outward from their body. These tasters are synesthetes, the true instinctual tasters. Here are three of them.

Sur Lucero, MS

Sur Lucero, MS, describes himself as an instinctual taster who learned how to work with the MS tasting grid only after many long months of hard work in order to pass the Master’s tasting exam in the summer of 2012. Sur is also one of 16 individuals to ever receive the Remi Krug Cup for passing all three parts of the exam on his first attempt. Lucero told me that he’s never relied on the aromatic and taste profiles that most students use, but more from the “picture” of a wine in terms of how it interact texturally on his palate.

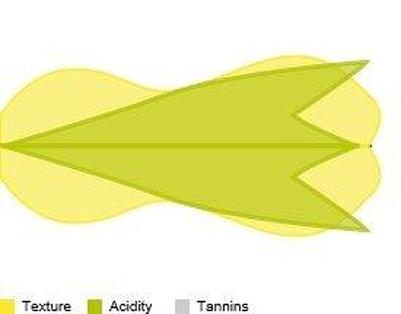

“I visualize how the wine feels on my palate,” he says; “whether it feels flat, lifted, vibrant, tense, or youthful.” When asked for an example he mentioned New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc describing it as an “intense wine with lots of energy and crisp angularity to it with shades of green, yellow, and platinum.” I asked if he saw shapes; he replied that he doesn’t necessarily see shapes, but does see colors and movement in what he described as a linear fashion out in front of him. “They move and they’re not just in one dimension. They expand on an X and a Y axis.” Further, he went on to say that the shape of a wine is largely determined by the structure. To Sur, the “intensity, the sharpness, and austerity” of a wine will create more lift on the Y axis as opposed to a wine that’s richer, fuller, and fatter which be more expansive and broader on the X axis.

I wanted to know how he was able to assess the quality of the fruit or age of a wine. He answered by saying, “The colors are generally based on the ripeness of the fruit. Leaner, tauter wines are going to have lighter shades of color. A New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc is a pretty intense, almost electric green. For Chablis, it’s a very pale cream straw; almost transparent.” Further, “I get the aromatic properties in terms of the fruit composition generally from the shades of colors that I see moving within the X and Y axes. Again, I don’t necessarily see cherries or blueberries or other specific fruits, I see shades of colors on the X and Y axes. But I don’t really think of the X and y axes as being present in this picture, I just see the shapes of the colors and how they move; the richer wines have more volume and the leaner wines have more height.” I asked him where a shape comes from and he replied with the following: “It comes from my chest and my head. Whenever I smell something I can feel it coming from here (motioning from his chest up to his face), definitely the upper part of my body.”

Gilian Handelman

Gilian Handelman is director of education for Kendall-Jackson. She’s long known that she doesn’t process wine the same way that most people do. During our session, I asked her how she was able to recognize a specific fruit vs. another. She replied by saying, “I guess it’s just an instantaneous reaction in my brain. There’s this thought that I’ve catalogued all these smells, and there’s a synapse that’s telling me this is dark fruit. It’s almost like electricity. Once I make those quick decisions, say that it’s in the black fruit world, I’m asking if it’s fresh black fruit or prunes or whatever.”

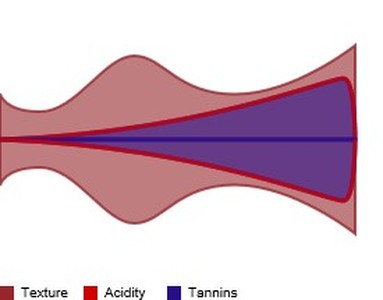

While saying the previous, she was motioning with her hands out in front of her face. I asked her if her hand movements corresponded to images of the aromatics she was smelling in the wine. She replied saying, “No, I think they are lines or shapes that connect in my brain leading me to one framework or another. I haven’t really articulated this before, but for me it’s sort of a family tree or a logarithm, almost like electricity.” As for the shapes, she said that the quality of the fruit and structure of a wine had a lot to do with determining the kind of shape. She described her experience of the RDV Cabernet from Virginia we were tasting as:

“It’s like a big rubber casing that’s filled and things are shooting out the end of the casing making the rubber stretch … then in the back there’s this kind of roller coaster and other stuff stretching through the casing. But there’s also like a cascade of what’s going on. There’s tannin and acid, and it (cascade shape) goes up (she motioned with her hands) coming back down and then goes up again.”

When I asked her if the shapes were consistent within a single grape variety she responded by saying, “It’s not that clear cut for me. It’s more like thought flowing into shape. So round, black fruit that’s kind of stewed like in this wine is amorphous. In fact, all the fruits I smell will go into those kind of roles. Maybe that’s what it’s like for me, a channel of shape and sound. So (speaking in a high voice) this is a tiny channel that is bristly, high-noted and cleaver-shaped. Then (speaking in a much lower voice) this amorphous pool of a shape.”

Gilian also experiences different sounds with different styles of wines. For her, a rich, round wine like the Cabernet we were tasting sounded like “gloop, gloop, gloop” vs. a lighter-bodied, high-acid wine like German Riesling, which would sound more like water lapping on the edge of a lake or pond. She describes it with the sound, “fffft, ffft, ffft.” She further said, “I see and hear music a lot when I taste. For me, wine we’re tasting is more like a basso sound (hums) vs. a higher sound.”

I asked her where a shape would come from and she replied, “It comes from my whole body. It’s really a three-dimensional model of my palate.” She went on to say that the shapes are outlines and some, but not all, have color to them.

Gilian has illustrated many of the shapes for different grapes and they can be found at the KJ website: http://www.kj.com/sensory-tour

Here are some examples:

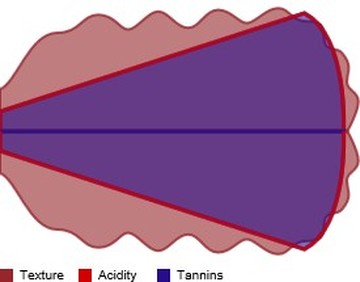

Like Gilian Handelman, Roland Micu, MS, has always known that the way he tastes wine is different from everyone else. As soon as we started his interview Roland said, “I smell the wine and then there’s this so-called shape or texture. Maybe it’s a type of synesthesia because if you hear a note on a keyboard, it’s going to have a kind of impact. All the notes are going to have different impacts. So the shapes or textures remind me of that.”

I asked him if the different components in a wine like a specific fruit had different shapes. He responded yes and then described the dark plum note in the Merlot blend we were tasting as having a round shape that was black in color. But his experience of the shape was more complex in that it had texture as if he were biting into the actual fruit. He went on to say that “different fruits have different textures. Raspberry is going have more angularity and be mushier. A dark cherry will be more focused and a dark plum more broad.”

I asked if images were involved in his perception of the different aromatics. He said yes but that the shapes were the initial sensation before an image of something would appear. Further, he said that the two were almost simultaneous as the process unfolds rapidly when he smells a glass of wine. He went on to describe the Merlot blend we were tasting with the following: “To me this wine is like a level. There are no sharp angles and texturally nothing shoots out. It’s not like a contact lens but more like squished elliptical shape and the edges are round.”

I asked him where the shapes come from and he said, “It’s a feeling and it comes out of me (pointing to his chest) then moves up through my chest and out through my eyes so I can see it and translate it.” In terms of assessing the kind and quality of the fruit, he said that “the shape is being formed and all these fruits are being assessed at the same time.”

Roland described any changes in the wine from the nose to the palate with the following: “I think with the nose its two dimensional, but when it gets to the palate it becomes three dimensional. It also might be more blocky or pixilated. But it’s three dimensional as opposed to the nose where it’s an image of a cherry or whatever.” As for assessing the structure in the wine we were tasting during the session, Roland used the shape to calibrate the amount of alcohol, acid, and tannin. “I don’t base structure on texture, but I’ve done some research and found that the elliptical shape in this wine typically is related to higher alcohol, riper fruit, new oak (usually barrique), and minimal minerality.”

Take Aways

Ultimately, the purpose of my tasting project is to model best practices by deconstructing the internal strategies used by top tasters. The end goal is to take the best strategies and be able to teach them to anyone interested in learning about wine. With that, the question of what can be taken from the strategies of Gilian, Roland, and Sur arises. At this point I’m not convinced their strategies can be easily taught. Perhaps what we can gain from them is the idea of using colors, sounds, and shapes to more intimately and personally calibrate the different aromatic and structural properties in wine. More than that, working with tasters like Sur, Gilian, and Roland makes me think about how complex and miraculous the human mind is. And though we share common “hardware” in the form of our brain and nervous system, how different we all are and how important it is that we celebrate these differences and learn from each other—on a blue day or any other.

nn