n

Broadbent passed the Master of Wine examination in 1960 in London. He moved to Christie’s auction house in 1966 and launched their first fine wine auctions. He remained with Christie’s until 1992 and was a senior consultant with them until 2009. During his time at Christie’s, no one tasted more fine and rare wine, or wrote so eloquently about it than Broadbent. His books about tasting and rare wine have long been industry benchmarks. I can’t recall the number of times when a need for information or a tasting note for an older vintage of Madeira or Port would have me reaching for Vintage Wine or The New Great Vintage Wine Book.

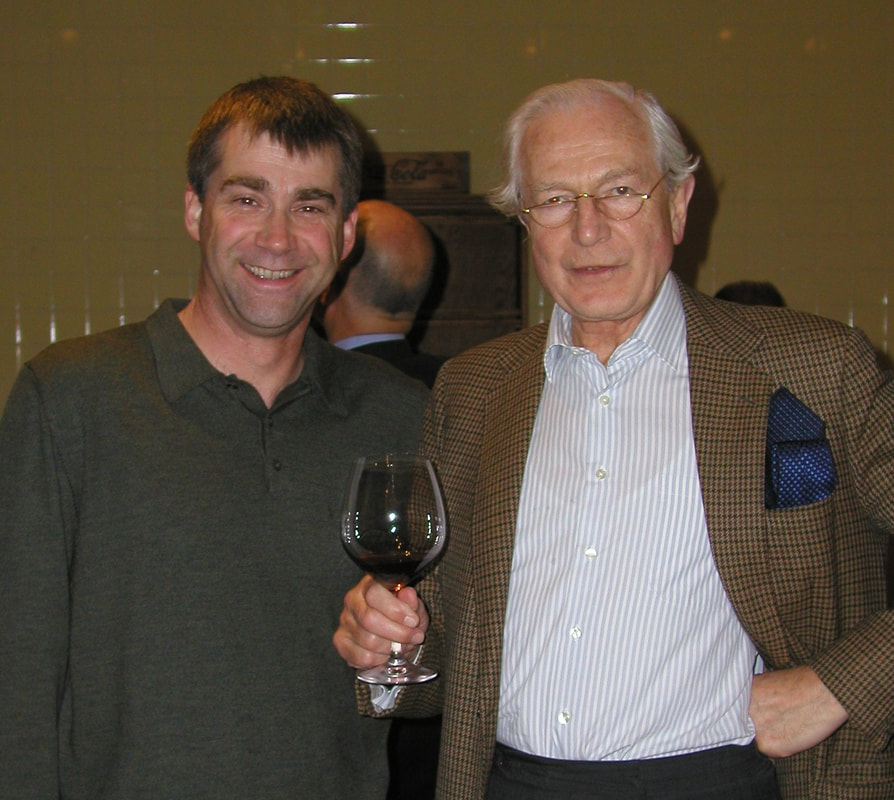

Michael touched the lives of countless in the industry. No doubt many have stories about him and I look forward to reading them in the days and weeks to come. I had one unforgettable encounter with Mr. Broadbent. It went something like this.

In the fall of 2002, I was invited by good friend Joe Bilman to be part of a dinner honoring Broadbent and his son Bartholomew. Bilman owns Subterraneum, a wine storage facility in Oakland. I’d worked with Joe in the restaurant business in San Francisco previously and had been one of his first customers, storing my cellar with him early on. In time, many collectors in the Bay Area did likewise and Subterraneum flourished.

At this particular time, Michael Broadbent had just released his book, Vintage Wine, and was doing a tour of sorts through the U.S. Joe knew Bartholomew and was able to convince him to have Michael do a book signing at Subterraneum followed by a catered dinner for the Broadbents and a small group of collectors who were wine storage clients. I should also note that I knew Bartholomew. In my previous role as one of the buyers at Virtual Vineyards/the original wine.com, I got to know Bartholomew well and bought copious quantities of Port, Madeira, and Portuguese table wines from him.

Joe extended an invitation to the dinner with the caveat that I had to contribute a bottle worthy of the occasion; no easy task given the cellars of the other guests. In a pinch, I called Brent Wiest of Cellars International. Brent generously offered two half bottles of the 1983 JJ Prüm Wehlener Sonnenuhr Eiswein for a player to be named later. The bottles would be my contribution to the meal.

Meeting Michael Broadbent that afternoon was a moment. He couldn’t have been more gracious. He was appreciative of the fact that I owned all his books and had already purchased the new book, which he quickly signed for me. For the moment all was well. It couldn’t have better. And then in an instant, things changed.

While I was chatting with Michael, one of the collectors who would be joining for dinner ambled up and placed a bottle in my hands. He said something like, “Joe said you’d take care of this for me,” and then wandered off. Broadbent looked down at the bottle and exclaimed, “Oh, the 1876 Gruaud-Larose! How marvelous!” My head snapped down and sure enough, there in my hands was a bottle of 1876 Chateau Gruaud-Larose with the label in remarkably good shape. Broadbent immediately started talking about the 1876 vintage on the left bank in detail.

During an appropriate lull in the conversation, I excused myself and went to find Joe. I showed him the bottle and he said to go ahead and decant it. Mind you, the bottle had just been taken directly out of a storage locker and could not be stood upright lest the sediment be disturbed and the wine immediately rendered undrinkable. I then asked Joe what kind of equipment he had on site. A Screwpull? Ah-so? Decanting cradle or basket? He answered negative to all the above. But he did have a decanter and a candle. The only thing I had was a $10 waiter’s friend corkscrew with a black plastic handle. If not familiar, a waiter’s friend is the kind of corkscrew used by untold thousands of servers, bartenders, and sommeliers, the world over. It is the easiest to use, most effective corkscrew there is. That said, it is the very LAST corkscrew on planet earth one would use to open a bottle over a century old.

As I carefully positioned bottle, Michael told me that he had tasted the 1876 several times previously. Then, with his photographic memory, he began to tell me about each time he had tasted the wine; the place, the occasion, and how each bottle had showed. I, on the other hand, was trying to perform micro-surgery with a can opener. I lit the candle and set it out of the way. I then took the entire lead capsule off the neck of the bottle so I could see exactly what was happening with the cork when I started to remove it. Next, I wiped the top of the bottle clean making sure it was free of any mold. Taking a deep breath, I inserted the auger of the corkscrew into the top of the cork. I slowly twisted/inserted the auger of the corkscrew and then began the delicate task of removing the cork. All the while Michael continued with his detailed account of each of the bottles of the 1876. Truth be told, I tuned him out and was completely focused on the cork as it started to come out in minuscule increments. After an eternity the cork was completely out and miraculously in one piece. To be honest, I got lucky as the bottle must have been recorked at the chateau at some point during the 1950’s or ‘60’s.

From there it was all routine. I removed the cork from the auger of the corkscrew and put it aside on one of the napkins. I wiped out the inside of the neck and the top of the bottle thoroughly. Then I slowly and gently decanted the wine into the decanter, viewing the candle through the shoulder of the bottle to be mindful of any sediment (surprisingly, in the end there was very little sediment at all). I placed the bottle and decanter down and finally looked up. Broadbent was smiling. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, “young man, that’s one of the best jobs of decanting I have ever seen.” I simply nodded and mumbled my thanks, somehow resisting the urge to come completely unglued. I then found the bottle’s owner and handed him the bottle and decanter.

The dinner, a multi-course affair, was a great success. James Grandison, a friend of Joe’s, did the cooking and it was superb. I was drafted to do all the wine service and was more than happy to oblige. The lineup of wines from the various collectors’ cellars was the stuff of legend: a magnum of 1982 Krug vintage to start, 1947 Chateau Haut-Brion Blanc, the infamous bottle of 1876 Chateau Gruaud-Larose, 1996 Chateau Palmer, 1961 Chateau Cheval Blanc, 1978 Henri Jayer Vosne Romanée Les Brulées, the 1983 JJ Prüm Eiswein, and a bottle of 1900 d’Oliveiras Moscatel to finish the evening off.

Throughout the meal, Michael was asked to provide commentary about each of the wines served and he did so brilliantly and graciously. Toward the end of the meal I served the Prüm Eiswein. After pouring, Broadbent took a sip, looked up at me, and said, “perfection.” And it was.

The following year Michael wrote about the dinner in his column in the May 2003 issue of Decanter. He described the evening and the wines in detail. Here are his thoughts on the two wines of note:

“The first of the reds was Gruaud-Larose of a scarcely ever seen pre-phylloxera vintage, 1876. It had been recorked at the chateau and almost certainly emanated from Cordier’s sale at Christie’s in 1976. Palish, with orange-tinged maturity; its fragrance was discernible despite the initial whiff of banana skins and final relapse; tart and creaking yet remarkably good for its age and vintage. One has to make allowances.”

“Happily, along came a JJ Prüm Wehlener Sonnenuhr Eiswein of a favourite Mosel vintage of mine, 1983. Orange amber-gold; a scent of apricots and refreshing whiff of tangerine; sweet of course, caramelly, raisiny, chocolatey. What Parker might call ‘decadent’ and what I shall merely regard as unashamedly appealing. Perhaps we mean the same thing.”

Michael closed the column with a wonderful remark:

“So this is how half a dozen collectors show and share their wines – with friends, and generous to a fault.”

I think back to that night at Subterraneum, the dinner, and the brief time I was able to share with Michael. It is truly one of the highlights of my career—something I treasure. So Michael, here’s to you. Thank you for everything you did for our industry. It is beyond measure. You will be greatly missed. Cheers and Godspeed!

nn