n

One of the challenges in writing a meaningful tasting note is being able to separate one’s technical assessment of a given wine from emotional response. But the problem runs much deeper. Wine as an idiom has no inherent language. To compensate, we as an industry have over time shamelessly—and largely unconsciously—begged, borrowed, and mugged terms and nomenclature from other completely unrelated fields. The result is a messy pastiche of terminology with some parts based on cold science and others on poetry and whimsy. It’s like Hello Kitty trying to play free form jazz in a cold, unlit industrial lab.

Part of the language issue stems from the fact that anyone’s reaction to a wine always involves both objective and subjective experience. Few people have the awareness much less the training to separate the two. In an effort to create meaningful tasting notes, I’ll attempt to do just that.

Objective vs. Subjective in Wine

Last year I wrote a post on objective and subjective in wine (www.timgaiser.com/blog/objective-vs-subjective-in-tasting). The premise of the post is that too often we hear the phrase, “wine is all subjective,” which is simply not true. Certain elements in wine can be isolated, identified, and quantified through lab analysis. Those criteria are objective. Other elements in the wine experience are based on a taster’s unique and very personal life memories. These are subjective and will always be different for everyone.

Why is objective-subjective so important in the context of writing tasting notes? Because the florid language some consider the bane of notes is directly linked to the subjective aspects of wine. Personally, I believe the subjective in wine is not only relevant—it’s important. Aside from all the technical information, it’s the one part of a tasting note that allows a taster’s unique voice to shine through.

I have a proposed tasting note template of sorts. However, before offering my template, it might be useful–not to mention curious–to examine tasting notes from various famous wine luminarios of the past and present.

Tasting Notes Through History

Like fashion, tasting notes have changed dramatically over the ages. Exhibit “A,” British novelist and author William Makepeace Thackrey:

“Wine gives great pleasure, and every pleasure is of itself a good.”

Thackrey (1811-1863) was known for his satirical works. His quote above provides little, if any, actual description of a wine, and simply—and poetically—tells us that wine is part of a good life. I couldn’t agree more.

“Food without wine is a corpse; wine without food is a ghost…”

Andre Simon

Simon (1877-1970) was a bibliophile, gourmet, wine connoisseur, historian, and writer. He was born in Paris and went to London in 1902 as the English agent for the champagne house of Pommery and Greno. Simon wrote over 100 books and pamphlets on wine and food. His knowledge of both was described as encyclopedic.

“Terms frequently used to describe a particular aroma or bouquet are rancio, foxy, and flor-sherry.”

Amerine & Roessler

Maynard A. Amerine was a professor of enology at the U.C. Davis and Edward B. Roessler a professor of mathematics. Their book, “Modern Sensory Methods of Evaluating Wine,” was a landmark work on the sensory analysis of wine. However, the quote above requires anyone to define the terms before having a clue what they could possibly smell like. Even the staunchest critic might wince just a bit.

“Fresh cut green grass, bell pepper, eucalyptus, mint.”

Anne Noble

Noble is a sensory chemist and retired professor also at U.C. Davis. During her tenure at the school’s department of viticulture and enology, she invented the “Aroma Wheel,” which has long been an influential learning tool for wine education. That said, I can already hear the critics beginning to gnash their teeth with the use of non-technical verbiage. After all, how can wine could possibly smell like other things?

And finally, Robert Parker:

“This Cote Rotie-like effort displays remarkable floral/lavender characteristics along with a dense purple color and an awesome bouquet of spring flowers, blueberries, blackberries and white chocolate. It hits the palate with a crescendo of intense, ripe, concentrated black fruits interwoven with barrique, charcoal and burning ember-like flavors. With staggering quality and full body as well as modest alcohol (14.2%) for a wine of such great ripeness, this riveting 2007 Syrah should provide immense pleasure over the next 15+ years. Don’t miss it!”

I had to include a Parker tasting note. This one is about a Washington State Syrah. Parker has long been a target of criticism for his writing. His notes, which are known for their voluptuous language, have actually been called soft core porn by detractors. In using descriptors like “awesome,” “staggering,” and “immense,” Parker has transformed the tasting experience into a full contact sensory sport. One might also conclude that a wine has to be staggering and immense to be good. And for the record, 14.2% is not modest alcohol. Ahem.

“The taste of alcohol counterbalances the taste of the acids.”

Emile Peynaud

Emile Peynaud (1912-2004) was–and still is–considered the Yoda of the winemaking world. His influence in teaching innumerable winemakers over many decades in the latter half of the 20th century can never be measured. Note his language here as completely technical. While straight forward for those of us in the industry, the description is not helpful to consumers.

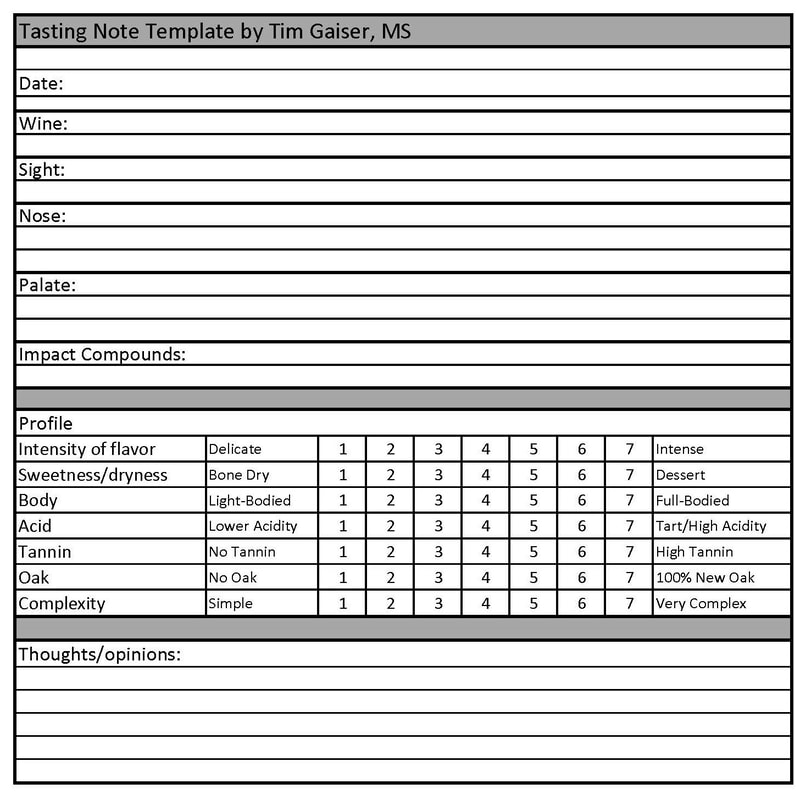

Back to square one. What’s needed for a useful tasting note? What form could a tasting note take that would include relevant information anyone in the industry and beyond can use (and hopefully understand), and yet at the same time allow the taster an opportunity to add their two cents? It’s a given that there will always be parts of any tasting note that are purely subjective vs. objective. Thus any template should provide an opportunity to record both. With that, here’s my proposed template. By no means is it written in stone. It’s meant as a point of departure. The intent is to create a straight forward yet concise form that enables one to consistently communicate about the delightful shared hallucination we call tasting wine.

I. The Basics

First, my template has a place to record the basics; what the wine looks, smells, and tastes like.

Visual: what color is the wine? There are different scales for wine color but practically any color can easily be understood by a reader. The clarity of the wine (or lack thereof) should also be noted.

Nose: includes descriptors of the fruit, fruit character or quality, other-than-fruit, earth-mineral, and the use of wood.

Palate: confirms what’s been already smelled and speaks to the structural aspects of the wine–acidity, alcohol, tannin, and phenolic bitterness—and can include one’s impression of the texture, balance, and finish of the wine.

Impact Compounds: highlights important compounds such as terpenes, Brett, and others which make certain wines typical in style. For example, carbonic maceration and stem inclusion in a Beaujolais Villages, or lees contact, ML, and oak usage in a Chardonnay.

II. Wine Profiles: Numbers with Meaning

Most everything listed above is commonly found in most tasting notes. The next segment of my proposal is definitely not—but it’s desperately needed. It’s a short profile that easily communicates the important information about a wine’s character and physical make up in terms of intensity, sweetness, the use of oak, and more.

All credit here goes to good friend and fellow Master, Peter Granoff. In the summer of 1994 Peter opened the cyber doors to Virtual Vineyards with his brother-in-law Robert Olson. Virtual Vineyards was not only the first online wine retail “shop,” but the very first online retailer of any kind. Peter and Robert literally started Virtual Vineyards on a server in Olson’s garage.

To avoid using numeric scores, Peter devised a system to convey the most important information about every wine that would appear in the Virtual Vineyards portfolio. His system used seven criteria to profile each wine: intensity of flavor, body, sweetness/dryness, acidity, tannin, oak, and complexity. Further, these seven criteria were represented in one-through-seven increments with one representing least/none and seven the most or maximum.

For example, with sweetness or dryness, Peter’s chart lists “bone dry” at one end with dessert sweet at the other. For intensity of flavor, the chart ranges from “delicate” at number one to “intense” at number seven.

Note Peter’s very conscious decision NOT to use a 1-10 scale simply because it would be too easy to extrapolate any number into a base 10 score—which he was trying to avoid at all costs. The results looked something like this:

Intensity of flavor – Delicate: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Intense

Sweetness/dryness – Bone dry: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dessert

Body – Light-bodied: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Full-bodied

Acid – Light acidity: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tart acidity

Tannin – No tannin: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 High tannin

Oak – No oak: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 100% new oak

Complexity – simple: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Very complex

As mentioned, all the wines listed in the Virtual Vineyards portfolio were profiled with Peter’s tasting chart. In addition, tasting notes were added that included descriptors for the wine, some of which were quite subjective. Technical information was included, if available, and a bit about the winery. Suggested food pairings were often included as well.

I joined Peter at Virtual Vineyards in 1996 and worked with him for five years until the company’s tragic demise in April of 2001. It’s worth noting that Virtual Vineyards/the original wine.com sold over $50 million of wine in five years using Peter’s system–and without ever using a single numerical score.

III. Wrapping It Up: Thoughts, Impressions, and Opinions

The last segment of my template is a space for personal thoughts and opinions about the wine. The remarks could range from varietal typicity, winemaking, and vintage character to simply whether the taster either likes, loves, or loathes the wine. True this is also where things can easily get florid and messy in a heartbeat. But again, I believe it’s absolutely necessary for the taster to be able to record and share their personal impressions about any given wine.

Now for the template itself. I’ve formatted a document that provides ample opportunities for recording what’s technically in the glass, uses Peter’s profile, and includes a place for opinions, musings, and more.

Tasting notes will always be a genteel battleground of sorts, where parties quickly establish polar opposites in their wine writing philosophy. It’s yet another example of the beautiful imprecision of wine. Hopefully my template will help ease the conflict or at least create some constructive dialogue. And that is a wonderful thing indeed. Cheers!

nn