Truth be told, it wasn’t my first job. That job would have been the summer before when my older brother Tom and I chopped cotton for a week on my Grandma’s farm. I’m not sure whose idea it was to enlist the two of us for five days of slave labor. Regardless, we earned a whopping $12 a day totaling to $60 for the week. But the job kept us out of everyone’s hair. We also got a wicked farmer’s tan.

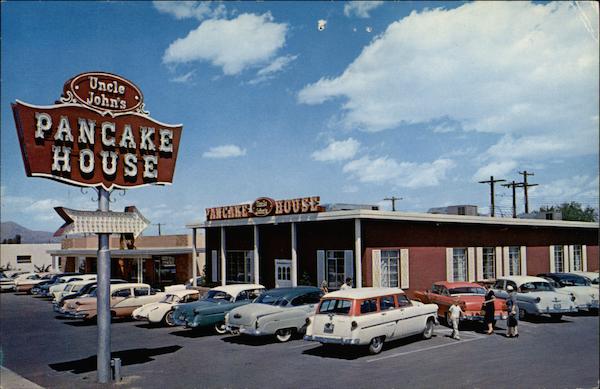

Even though $60 seemed like a windfall at the time, it didn’t begin to cover the cost of a new trumpet. Any pitch I made for the parents helping me buy a new ax—which would have cost between $500 and $600–failed to launch. They simply didn’t have the money. After school let out in May the following year, I applied for and got the job at Uncle John’s. But there was a slight catch: the hours were Wednesdays through Saturdays, 6:00 PM to 4:00 AM. That’s right, ten hour shifts for four consecutive days.

It goes without saying that this kind of nonsense wouldn’t legally be tolerated now. Today, the state labor board would slap the owners of the restaurant sideways into tomorrow if they caught wind of anything remotely resembling such skewed scheduling practices. But this was 1971 and indentured pancake servitude wasn’t unusual.

The restaurant’s manager was a woman named Darlene, a skinny, hard-edged, aging cowgirl who looked like she’d seen a lot of bad pavement. She was also a chain smoker, with a lit cigarette in hand sometimes even when on floor during service. Darlene had a serious case of helmet hair styled with enough Aqua Net to waterproof a dinghy. The finishing touches were enough cake makeup to fix the dented fender on a ‘59 Buick and a force field of some cheap screeching floral perfume. The sum total was that Darlene looked like Tammy Wynette’s evil twin. But she was an absolute shark in the restaurant, barking orders to the staff in both the front and the back of the house.

The waitresses were all lifers, older women who had worked at the restaurant for years. They constantly bitched about their tips, their feet, and Darlene. At first, they treated me like a mutt some relative had suddenly foisted on them. But in short order they discovered that I could make life at Uncle John’s much easier for them. And that, dear friends, was because I quickly discovered everything about bussing tables was squarely in my wheelhouse.

Allow me to explain.

The very definition of the job required speed, repetition, and thoroughness—all capabilities that, for whatever reason, I had in excess. But there was one more important element. After the first couple of shifts I realized that I had “restaurant eyes,” a sixth sense of sorts that meant I could walk through a section of the restaurant and instantly see what needed to be done on every table in the moment. To this day I can still walk through a restaurant and experience the same thing. It’s a curse at this point.

I also discovered I could easily keep at least a half-dozen things in mind that needed to be done in the next few minutes. More importantly, I could also prioritize them in regard to whatever needed to be done first. My list constantly changed, with things done going off and things needing to be done constantly added. Finally, my recipe for bussing success included the fact that I was a skinny piece of sushi who could move fast. More often than not I found myself refilling coffees or waters because I was out of things to do in the moment. Thus, in no time the aging wrecking crew of waitresses, who just days before would have chased me into rush hour traffic without a second thought, adopted me as their idiot bastard son.

Getting home after finishing up at 4:00 AM, however, was another matter. For the first week or so Dad insisted on picking me up, bike and all. However, Martin was 48 at the time and the last thing he wanted to do was get up at 3:30 in the morning and drive anywhere, much less retrieve me. After a short time I convinced him it would be OK. And frankly it was. I don’t recall any incident ever happening other than being chased by random stray dogs. I also marvel at the fact that I was never stopped by a police car. I chalk it all up to luck.

Like many 24-hour restaurants, Uncle John’s was a cross between a chameleon and a community theater for aliens at the edge of the universe. That is to say, its personality changed multiple times throughout the course of a day. At breakfast it was a greasy hash-slinging pancake-waffle joint serving up breakfast at light speed. That would change only slightly at lunch when regulars, who worked at nearby offices, had less than an hour to hoover sandwiches and the like.

Dinner was the slowest meal service of the day. Fortunately, location helped as the restaurant was on Central Avenue, part of the old Route 66 which traversed the entire length of the city. A good deal of dinner business was made up of hungry tourists passing through town not wanting to wait until Clines Corners on the other side of the mountains or the remotely distant Tucumcari to stop. Then there were the tour buses. Many times, one or more buses pulled up in front of the restaurant filled with Baptists headed to a convention somewhere in the deep south or army guys headed to a base in Texas. Then it was all hands on deck as half the restaurant would instantly get seated. In minutes the place would get slammed. First, the waitresses would be overwhelmed and then the kitchen would groan and creak under the weight of getting 20 or more orders at once.

At tour bus times I would take on the role of a rabid chihuahua busser, moving as fast as I could and trying to cover drinks, get sides, and clear plates as needed with the usual refilling of coffee, sodas, and water. In no time the checks would be paid and the hordes would reboard their buses bound for highway glory. Then the real work would begin with a massive cleanup and resetting of tables, not to mention the restrooms. Yes, busboys had to monitor the restrooms during their shift—even the ladies’ room. I got my first taste of cleaning public restrooms there, a curse that would follow me into college when I was a janitor at a Lutheran church for the better part of three years. But that’s another story.

If breakfast, lunch, and dinner were the first three acts of a psycho-waffle drama, the post-bar rush that started shortly after 1:30 AM was a bizarre Fellini-esque finale in which the babysitter turns into an evil clown, the aging banker suddenly disappears with all the potted plants, and the tragic anti-hero is pulled down to hell by the commendatore, who’s dressed in drag.

The cruel irony of it all was that the busiest—and craziest—part of the 10-hour shift happened after I’d been on my feet for almost eight hours. As soon as the clock struck 1:30 AM all the bars that dotted Central Ave. would start to give last call. Within minutes, the restaurant would be crammed to the gills with denizens of drink in every shape, size, and persuasion: sloppy businessmen, guys on a rowdy night out, college types, prostitutes, and much more. The noise was deafening and the cigarette and cigar smoke was thick. No surprise that after a night of boozing it up everyone was famished, and people wanted their steak and eggs, omelets, and strawberry pancakes RIGHT NOW.

Months later, when school started back up and my schedule was relegated to weekend mornings, I experienced the breakneck pace of breakfast service with its own flavor of triage. Bar rush service was all that and more because of the chaos created by a bunch of drunk, unruly customers. The amount of coffee I poured was astonishing. I could barely keep ahead of demand by brewing fresh pots. “These people are drunk,” I would think, “what the hell is all this coffee going to do?” In reality, the coffee served to create a much-needed buzz and metabolic momentum that would last just long enough for people to eat and then drive home, hopefully without getting into an accident.

The next day I told my Mom about Red and his job offer. “He sounds like a criminal and the last thing you should do is meet up with him.” I didn’t know about the criminal part but agreed with her about skipping the meeting. As always, her advice was spot-on and I didn’t give it another thought.

It was only a matter of time before Red made another appearance at the restaurant. When I approached the table to pour coffee he berated me, saying, “where the hell were you? Why didn’t you show up?” I explained that my Mom thought he was a dangerous criminal. Actually, I just told him I was happy with the current job and wasn’t looking for anything else. Then I scooted away from the table before he could say anything else. But every time I looked his way Red was glaring at me, giving me the evil eye, as were the young guys who were with him.

When I was leaving the restaurant that night I asked one of the cooks, a burly guy who’d just finished up a stint in the Navy, to walk outside with me to make sure Red and the boys weren’t waiting. Fortunately, the parking lot was empty. That was the last time I saw Red and his entourage. God only knows what he did. My sense was that he was into dealing drugs, stolen cars, or something even more unsavory.

Then there was Curley. By day he was a mechanic. By weekend night he raced cars on a dirt track. More than anything, Curley was a large mutant slob of a human with just enough intelligence to be annoying and/or dangerous. He was also a stereotypical bully who surrounded himself several miscreants who were even bigger losers. But Curley was also Darlene’s nephew, so he could do no wrong.

I only saw Curley and his gang after he raced on Friday and Saturday nights and after they had had too much cheap beer. Then Curley would come in, dirty racing gear and all, and hold court with his slackers at a large booth at the back of the restaurant. Approaching the table was dicey, to say the least. Pouring coffee was met with insults, jeers, and having crumpled paper napkins bounced off the side of your head. All the while Curley, covered in dried sweat and smears of grease, laughed like a donkey, showing off his two missing front teeth.

I quickly adapted the boxing strategy called “stick and move” whenever having to deal with Curley’s table. Meaning I would go in quickly while the lot of them were distracted, get done what I had to get done as quickly as possible, and then get the hell away from the table. It usually worked—but not always.

I thought I’d seen the last of Curley when I moved to weekend breakfast shifts months later. Sadly, not true. While washing dishes one Sunday morning I heard Curley’s donkey laugh outside in the restaurant. “Dear god, please don’t let that idiot back here,” I silently pleaded. But the almighty must have been busy with the church thing, it being Sunday morning and all. Minutes later Curley’s ugly toothless mug made its appearance. At that moment the other guy washing dishes and I were in the middle of cracking hundreds of eggs into a huge metal bowl that would be ferried to the cooks for omelets. After uttering several unintelligible insults, Curley spotted the tall stack of full egg cartoons. Instantly he grabbed eggs in both hands and started firing them at us, laughing hysterically. We had no recourse but to run out the back kitchen door in defense, only to have Curley go tell Darlene we were screwing around on the job. She immediately found us and read us the riot act, saying we would be fired the next time it happened. We tried to tell her what had happened but she refused to listen. I silently cursed her helmet hair–and Curley’s dumbass mug too.

I wasn’t long for Uncle John’s after the egg incident. I’d saved enough money to buy a trumpet and was getting too busy with school. But the place, with its brutal hours and wack-job cast of characters, was the quintessential first restaurant job. The first job where you learn if you can hack the work and if you’re properly wired for success in the business. During my time at Uncle John’s I discovered that I possessed the first and excelled at the second. Working there also gave me restaurant eyes and taught me how to move quickly and efficiently on the floor. Finally, bussing tables taught me how to store, prioritize, and accomplish tasks quickly and efficiently, something that continued to benefit me in every future restaurant gig and beyond.

As for Uncle John’s, at some point much later it closed down and the building was razed. But I still have fond and janky memories about the joint. It makes me think that there are two great equalizers in life: one is parenthood and the other is the restaurant business. Where anyone, regardless of skill or experience, can go down in flames. But where one can also be a star, especially between the hours of 6:00 PM and 4:00 AM on weekends.