n

of Chicago. He was 91. Herseth was the former principal trumpet in the Chicago Symphony—for 53 years. His name may be far from familiar, but to anyone in the brass world he was not only a living legend but one of the greatest, if not the greatest, orchestral trumpet players of the last century.

Herseth was born in Lake Park, Minnesota, the son of a band director who gave him his first trumpet. His first musical experience was playing trumpet and cornet in school bands and at music camps. He graduated from Luther College in Iowa with a degree in mathematics before playing with service bands during World War II. After the war he studied with Marcel Lafosse and Georges Mager at the New England Conservatory in Boston, with the expectation of eventually landing a high school or college teaching job. But while at the conservatory Herseth, received a telegram from Artur Rodzinski, who had just been named music director of the Chicago Symphony, asking him to come to New York and audition. He later recalled:

“I didn’t know much of the orchestral repertory at that time, so I checked out the trumpet parts for as much music as I could find in the libraries. Then I went down to Rodzinski’s apartment on Fifth Avenue and dumped the music on the rack of his grand piano in his enormous living room. I wasn’t nervous because I thought I was auditioning for the third-trumpet position. So you can imagine my surprise when, after listening to me for about an hour, he said, You will be the new first trumpet of the Chicago Symphony.”

The rest, as they say, is history, with Herseth assuming the principal trumpet chair at the beginning of the 1948 season and performing under six music directors over the next 50-plus years; directors that would include Rodzinski (1947-1948), Rafael Kubelik (1950-1953), Fritz Reiner (1953-1962), Jean Martinon (1963-1968), Sir Georg Solti (1969-1991), and Daniel Barenboim (1991-2006). It was during the Fritz Reiner years that the CSO brass section became one of the world’s finest, known for its brilliant, focused, and powerful sound. At the center of the section was Bud, whose playing became the standard for orchestral players and students for many generations to come.

On any given day, a really good player can completely take a dive and have a disastrous performance. I’ve seen it many times. Trumpet recitals, moreover, are something akin to gladiators vs. lions in the coliseum. When things go wrong, as in someone losing their “chops” or their endurance, the results are painful to hear much less witness. I’ve been there too. As for the other 10% for whom playing the trumpet comes easily, half get bored with it and give it up. The other half usually end up with careers and become names we know. Wynton Marsalis is a good example.

It’s no surprise then that the principal trumpet chair in a major orchestra is one of the most stressful jobs of any kind. I liken it to being a top closer in baseball, always throwing 95-plus mile-an-hour fastballs to the best hitters in the game. When you screw up the entire world knows it. For the principal trumpet, it’s much the same, playing the most difficult literature night in and night out with any mistake broadcasted at high volume to the listening audience, if not a radio audience of untold numbers. There is literally no place to hide and conductors expect perfection all the time. So Herseth’s tenure of five decades at the helm of the CSO’s brass section is all the more remarkable and literally without precedent.

Herseth’s playing combined consistency, precision, and power with an immense sound and impeccable musicianship. His recordings with the CSO were one of my go-to resources as a student when it came to getting an interpretation of an orchestral excerpt or just an example of great playing and a beautiful sound. Here’s a handful of my favorites, many recorded during the Reiner years.

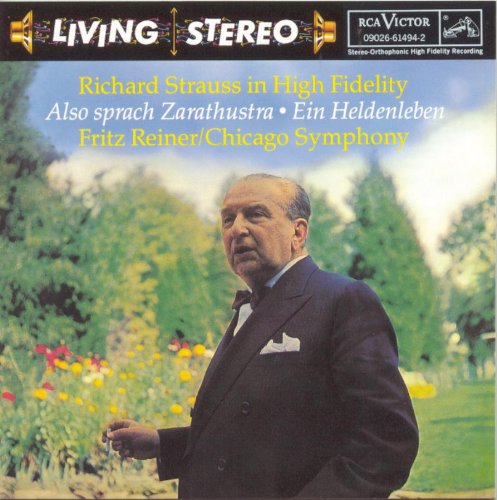

One of the great pieces of 20th century music and one of my very

favorite classical recordings. A tour-de-force of orchestral brass

playing.

The CSO recorded Mussogsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” six times and Reiner’s recording is widely considered the best.

During Solti’s tenure in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, the CSO became one of the most accomplished Mahler orchestras in the world. The fifth symphony became their signature piece and I was fortunate to hear them perform it in Davies Hall in San Francisco in 1987. It’s one of the great orchestral performances I’ve ever heard and Bud did not disappoint.

Scheherazade is one of the great “war horses” of the 19th century

repertoire. It’s rarely performed this well and the last movement here was recorded in one take—remarkable when you listen to how well it’s played.

CSO, Fritz Reiner

Two of Strauss’ greatest tone poems brilliantly played. And yes, the beginning of Also Sprach is the music from 2001: A Space Odyssey. There’s actually more than 30 minutes of music after that. Check it out. It’s pretty

good.

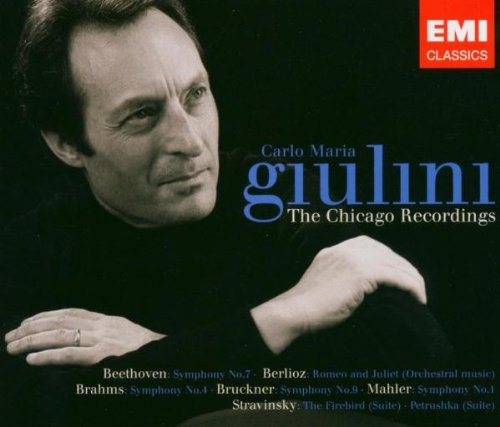

Giulini was the principal guest conductor with the CSO during the ‘70’s and made several outstanding recordings with the orchestra. This set is a great introduction to the CSO, with stellar performances of Brahams Symphony No. 4, Mahler Symphony No. 1, Stravinksy’s suites from the Firebird and Petrouchka, and Brucker Symphony No. 9.

Finally, here’s a You Tube clip of Daniel Barenboim conducting the CSO in a performance of the fourth movement of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony for the opening concert of Carnegie Hall’s 1997 season. It more than

demonstrates the virtuosity of the CSO brass section with Bud front and center—in his mid-seventies and entering his 49th season with the

orchestra.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLHj-eekdNU

nn