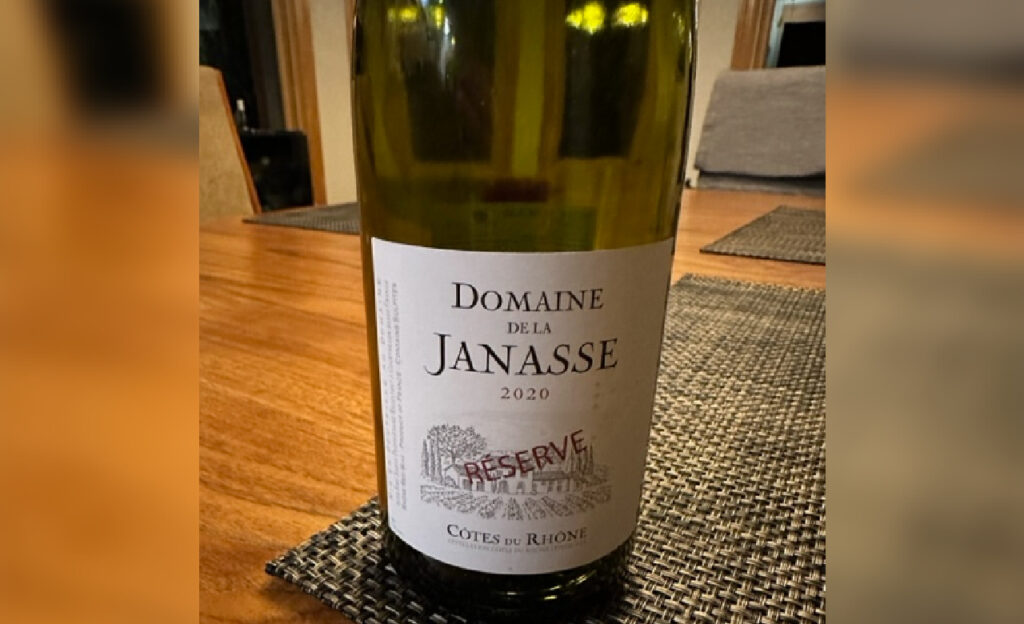

This morning I woke up with a bit of a headache. That may not sound unusual, but it is. Thankfully, I rarely get headaches. The ones I do get usually precede an ailment of some kind like a cold, or they follow an initial pain in the bumpkus after too much driving in Rio Rancho traffic. That’s another story. This morning’s headache may have its roots in the wine we enjoyed with last night’s dinner. It was on the strong side. Strong as in high alcohol content. The suspect in question was the 2020 Domaine de la Janasse Côtes du Rhone Reserve, pictured above.

The word “reserve” tacked on to the name is very un-Rhône-like, and something infrequently found on the label of a French wine. If anything, it was appended to the name by the importer in order to register the wine using more than one label in an effort to appease the TTB overlords (Trade and Tax Bureaus) for interstate shipping purposes. Sometimes producers also use the word “reserve” on the label so they can work with more than one importer. But you didn’t need to know all that. What might be useful concerning the previously mentioned headache is to know that the wine in question weighed in at 15% ABV (alcohol by volume).

A note about the number on the bottle. Typically, the ABV on a bottle of Côtes du Rhone rouge is between 13.5% and 14.5%, and usually at the top end of that range. In which case, 15% is high. It’s actually high for any non-fortified wine, the latter being Port, Sherry, or Madeira. But the world is changing, as Galadriel said at the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring. At least in Peter Jackson’s brilliant screen adaptation of the book. In the wine world, things have changed and continue to change because of global warming/climate change. The Southern Rhône has always been a warm place. It’s getting warmer now. Which means the annual growing cycle of grape vines is being pushed forward by weeks with harvest starting in August vs. the historic September into October. That means grapes are getting riper, and riper grapes mean higher alcohol in the wines. Hence the 15% number on the bottle. In the glass of red wine, high ABV makes itself known in the form of pruney-raisinated aromas and flavors. I’m also sensitive to alcohol and immediately experienced heat when I first smelled the wine.

One more thing about the ABV number on the bottle. Sheep tell lies. Sorry, old high school joke. Actually, wineries often under-report alcohol levels in their wines. This because the federal tax rate for any wine over 14% ABV goes up by almost 50% per gallon. Funny thing is that federal law also allows for wineries to underreport the ABV on a bottle by as much as 1.5%. As if anyone would ever do that.

Faux-outrage over higher alcohol in wines, especially red wines, goes back decades. In the early 90s, alcohol levels in wine first started to creep up, most notably in California Cabernet. In short order the critics cried foul in the style of Dylan Thomas (rage, rage, against the dying of the light, etc.). There were many factors contributing to the higher numbers, among them certain wine writers who used the 100-point scoring system. Said writers rewarded the new riper style of wines with higher scores. No surprise winemakers and winery owners paid close attention with some quickly making a shift towards emulating the riper style in hopes of receiving higher numbers.

Other things contributed to higher ABV numbers. First, climate change in the form of warmer mean temperatures during the growing season, not to mention dramatic changes in weather patterns including cycles of drought and flooding. Second—and just as important—new plant material in the vineyards. After phylloxera decimated wine regions throughout California in the 80s and early 90s, owners were faced with having to replant at great expense. As a result, a good deal of thought went into matching appropriate grape varieties to specific sites and soil types, as well as in choosing phylloxera-resistant rootstocks and improved vine clones. The new and healthier plant material meant longer potential hang time for the fruit. With that came higher sugar levels in the grapes making for higher alcohol in the finish wines. All a straight forward equation.

A quick look back to average ABV numbers on pre-1980s Napa Cabernet confirms the above. More often than not, the alcohol listed on the label then was 13.5% or below. In the 60s it was even lower—sometimes 12%. Regardless, the fruit in these wines was generally ripe and the wines were balanced. The key word here is balanced.

Numbers on the bottle don’t always tell the entire story. Regardless of ABV level, a quality wine is always balanced. Specifically, a balance between fruit ripeness and acidity. I call it the “sweet-tart” factor, in homage a favorite tooth-decaying candy of my youth. Regardless of color or kind, any quality table wine must have a good fruit-acid balance. In that context, the fruit can be ripe—even over-ripe, but there has to be more than enough acidity to balance it. If needed, acidity can be added. In fact, many red wines from warm climate places like California and Australia are often acidulated or acidified (both mean the same). Specifically, they have added tartaric acid in powdered form. Before anyone gets dangerously excited, the tartaric acid used is derived from grapes. No harm no foul.

Back in the day there was a learning curve with acidulation. A commonly heard complaint about the first several generations of riper-style wines was that they tasted sharp from tartaric acid added in an attempt to balance the high alcohol and riper fruit. Timing with acidulation, as with anything in with winemaking, is everything. One can acidulate at the crush pad, during fermentation, after fermentation, or just before bottling. The first three are by far preferred. The third will often create the baby aspirin in the mid-palate taste and texture of the wine that was the source of the complaints.

Back to the Janasse Cote du Rhône from last night. Despite the ripe/raisiny character, it was delicious because it was balanced. That was partly due to the wine being made from a blend of grapes, some of which retained high natural acidity even though fully ripe. But the wine’s inherent quality was due to its pedigree. Domaine Janasse is an outstanding producer of Châteauneuf du Pape. A quick look on their website revealed that the domain produces five different Châteauneufs, four red and one white, as well as the Côtes du Rhone in question. Odds are the latter is declassified Châteauneuf or wine made from the estate’s younger vines. A word to the wise about that—and a wine tip. Estate-type wines from quality producers are almost always a cut above. They’re usually good values as well. This also holds true for estate Rieslings from top German producers, be they dry or fruity (off-dry) in style.

I’ve always been a fan of Châteauneuf du Pape. To me, it’s quintessential Mediterranean red wine with its savory, peppery, herbal, and earthy qualities—not to mention the lush warmth of Grenache, which accounts for much of the blend. However, many moons ago when I was studying for the MS tasting exams, I struggled with getting Châteauneuf du Pape and its neighbor Gigondas, calling them everything from Chianti Classico to Rioja Gran Reserva. Now it would be like mistaking Elvis for Beyoncé. But at the time, the missing part of the equation was the fact that both were blends and not based on a single variety. Finally, one day after missing a call on a Châteauneuf for the umpteenth time, it occurred to me that the wine didn’t taste like any one thing—as in a single grape. Instead, it tasted like a blend. I know what you’re thinking. Who gave you the PhD in doy-yoy? The good news is that from then on, I got the wine. Tasting conundrums aside, it’s time to connect the dots, land the plane, and otherwise reveal the mystery behind the title of this post. Ultimately, one’s liver trumps all. Literally. With age, one’s liver doesn’t process alcohol as quicky or as well as it once did in the flower of youth. Hence 2.5 glasses—a half-bottle—of a high alcohol wine registers with the big “L” as a sluggish metabolism and a dull ache in the back of the skull the next morning. And it’s not even like I had two margaritas. But don’t worry. No heavy equipment was operated during the writing of this post. With that, a catchy Latin title seemed like a good idea. Something like Vetus Vinous Wimpus, which roughly translates as “aging wine wimp.” Now you know. Cheers.