n

I completely agree with Asimov. At this time, expertise on practically any given subject is not only not getting its due–it’s being roundly criticized and even gleefully assaulted. In regards to wine, the answer is a perfect storm of multiple factors:

- The wine culture in the U.S. is still relatively young—35-40 years at most.

- There is a puritanical anti-alcohol sentiment in our culture, the origin of which predates our country’s beginnings.

- A sizeable percentage of the U.S. population never consumes alcoholic beverages due to religious or other reasons. Further, this same demographic seems categorically incapable of separating wine from spirits in regards to context and consumption. All alcohol is considered “evil” to some degree.

- Interest in fine dining, cooking, and eating healthy is still the exception and not the rule. An alarming percentage of Americans routinely consume processed, boxed, canned, frozen, and fast foods. Beverages at table during a meal could be anything from soft drinks, coffee, tea, or energy drinks. The current health and obesity crises? No surprise.

- Olfactory memory is simply not important—or valued–in our culture. Anyone who works in or writes about an industry requiring a high level of olfactory expertise such as wine, beer, spirits, or perfume is always viewed with great suspicion. The fact that someone who is a trained professional with years—even decades—of experience and can smell “things” in a glass of wine, or vial of perfume for that matter, is not taken seriously. The common accusation is that they—as in we–are making it all up.

- Wine has no inherent vocabulary. Over time the industry has begged, borrowed, and stolen terms from other completely unrelated fields. The result is a patchwork of verbiage destined to create confusion and disagreement—just within our industry. Viewed from the outside, wine vocabulary and descriptions are seen as alien language.

In the end, perhaps we in the industry are partly to blame for the dilemma. I say this because we generally have never defined what it is we actually do as professionals, specifically in regards to tasting. Things might improve—no guarantees here—if we define what a professional taster actually does. So with the noble intent of clarifying some very murky waters, I offer the following: a working definition of what wine professionals do, what we don’t or can’t do, and finally, yes, how we can be fooled.

We are trained to analyze and assess wine for the following:

- Balance and quality—or the lack thereof—at any level.

- Typicity in classic grapes and wines, and can do so in most cases with a great deal of consistency.

- Recognizing common wine faults—even in trace amounts–and further how and why some of those “faults” are contextual depending on the specific wine.

- Knowing cause and effect in regards to why a wine looks, smells, and tastes the way it does.

- Recognizing impact compounds—a subset of the most important aromatics and flavors—that are crucial to identifying classic grapes and wines and help with assessing typicity.

- Calibrating structural elements—the levels of alcohol, acidity, and tannin–in a given wine with accuracy and consistency. Further, using structural levels to assess the quality and typicity of a wine.

- Further, we study producers, regions, classifications, and vintages over a duration of time—as in, our entire careers.

- With experience, the tasting process becomes almost entirely objective. The more experience one has, the more objective tasting becomes–and vice-versa.

- Ultimately, we taste thousands of wines—even tens of thousands—over a long duration of time and know exponentially more about wine on multiple levels than practically any consumer. Period.

Does all the above mean you can hand us a completely random glass of wine on the fly and we’ll know exactly what it is? The answer is a resounding no. There are over 100,000 wines commercially produced every year. The expectation that someone can taste any wine blind and always be able to identify it is somewhere between ludicrous and moronic. However, that doesn’t stop Asimov from commenting on blind tasting in the same column:

“The height of understanding wine nowadays seems, in popular culture at least, to be the ability to guess the identity of a wine served blind. It’s essentially a useless skill, a parlor game in the wine trade, yet it contributes to the notion that to understand and enjoy wine requires special powers.”

My response: nothing could be further from the truth. Blind tasting, at least in the context of deductive tasting used in the M.S. curriculum, is a highly disciplined exercise that requires a great deal of experience and skill. Preparation for M.S. tasting exams requires that the student first memorize a tasting grid with over 40 criteria and then master multiple concepts including many listed above; cause and effect, impact compounds, calibrating structural elements, knowing markers for classic grapes and wines, and considerable theory study. A parlor game? Hardly. It’s monumentally difficult. The pass rate for the Master’s tasting exam historically ranges between 8-15%. There’s a reason why.

We Can Be Fooled

That being said, we as professionals can be fooled. The “instruments” of our trade—as in, our nose and palate—are part of our physical body and thus subject to change every day (even during the course of a day) given how we physically and emotionally feel.

Add to that the fact that context trumps everything. There are three variables in every tasting experience: the wine, the taster, and the context. Anything involved in the tasting including the glassware, the room, the tasting environment, the lighting, extraneous noises and odors, and more is part of the context. Change the context of a tasting and you change the tasting itself—sometimes dramatically.

For example, tell a panel of industry professionals they’ll be tasting a flight of Bordeaux blind and slip a mass-produced Cabernet into the lineup. There is always a possibility that some on the panel might miss the commercial wine. Why? Because the idea of tasting Bordeaux creates such powerful expectations based on previous experience and memory. No surprise that some might taste the mass-produced wine and think, “Wow, this is really terrible Bordeaux.”

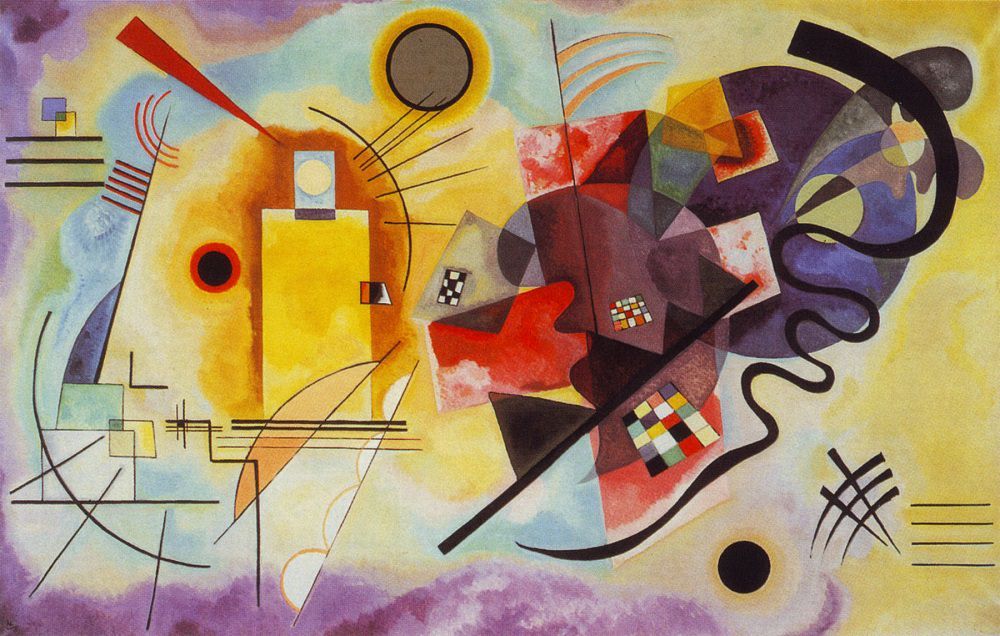

It’s like the age-old pointless exercise of asking someone to look at a photograph for several minutes with the instruction to remember all the blue objects in the image—and then asking about red objects after the fact. Change the context in any way and change the experience. For the record, I have no patience with this kind of bullshit. Which brings me to my next point.

As much as we try to make wine accessible to the public (and we absolutely need keep trying to make wine accessible to the public), wine is anything but easy. There is so much to know about wine on so many different levels that no one human being can possibly keep up with it.

The music-wine comparison might actually be valid here. Consider the range of styles in music. On one side are childhood songs and commercial pop music; a late Beethoven quartet is at the other. What can we take from these two extremes? Both are music. Both are in their own way relevant and have their respective places in the vast musical universe. Both are also about personal preferences and experience. And both are ultimately NOT of the same quality.

Wine is the same. It ranges from mass-produced commercial product packaged in boxes, jugs, cans, and tetra packs all the way to single-vineyard domain-produced bottlings made in minuscule quantities. Like music, the range of styles is extreme. Once again, both are equally relevant in that they are wine and appeal to different markets. And like music, every wine is definitely not of equal quality–which brings us back to what wine professionals do: we analyze and assess wine for quality regardless of the price point.

One further point about the music-wine comparison. One may choose over time to learn more about music—or wine. In doing so, one’s taste in either will inevitably change. In wine, one’s palate can and will change multiple times over a career arriving at a preferred style completely opposite to one’s first experiences. As Shakespeare wrote in “Twelfth Night,”

“A man loves the meat in his youth that he cannot endure in his age.”

Coda

I will end with one last quote from Asimov’s column:

“In the populist vision, the critic is simultaneously fastidious and intimidating, comic and sinister. Wine is the official beverage of the sneering elites, who think they are smarter and better than everybody else, and thus is a natural target for fear and resentment.”

Asimov leaves us with a challenge: the onus will forever be on us in the industry (including Asimov) to call out “snobbism” and wine errors in the media whenever we can. Collectively we need to keep trying to change the image. It won’t happen overnight, but it is the good fight.

nn